Arrays, Memory, and Pointers#

In this chapter, we start by looking at arrays, a fundamental data structure in C++. In order to properly understand arrays, we need to learn more about memory handling, which in turn motivates the next topic: pointers.

Arrays#

In Introduction to C++, we covered the vector data type, which behaves similarly to a Python list. However, arrays are fundamental data structures in C++, so they are lower-level when compared to vectors. The reader might be familiar with Python’s NumPy arrays, and while these are based on C arrays (which is why we call them NumPy arrays), they have additional built-in functionalities. The arrays we will talk about here are low-level structures, making them fairly “primitive” but also efficient.

What is an array?#

An array is a sequence of elements stored contiguously in memory. Contiguously means that each element follows the other directly in memory. Machine hardware can more effectively access and iterate over contiguous memory, making arrays efficient in both speed and size. Because the elements are stored contiguously, an array takes up a given chunk of memory, and we cannot generally shrink or expand it, as there is no guarantee that the memory we want to expand into is available. In addition, all elements in an array have to be of the same data type. While all of these properties might sound restrictive, they are what leads to arrays being so efficient.

To summarize, arrays are:

A fixed-size sequence of elements of a single data type

Stored contiguously in memory

Highly efficient

Creating an empty array#

Unlike the vector data type, arrays are built into C++, and we do not need to include anything to use them, as they are actually a C data type.

As mentioned, all elements of an array have to be of the same data type, and the array size has to be fixed. The following is an example of declaring an array’s type and number of elements

double x[100];

This would create an empty array of doubles with 100 elements. Note that despite specifying the data type as double, we are making an array of doubles, which is apparent from the square brackets.

It would be natural to expect that all 100 elements were initialized as 0, but this is not the case. Instead, when we define the array, the memory required to store the 100 doubles is requested from the system, and this memory is allocated, meaning it is made available. Whatever was stored in that allocated memory address is not changed, so the initial values of the elements are the previous content in that memory. The array’s initial values are then effectively random, as illustrated below, unless specific initial values are passed

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int n = 20;

double x[n];

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

std::cout << x[i] << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

A previous execution of the above code yielded

6.9138e-310

...

2.12203e-314

If we want an array to be initialized and filled with zeros, we need to do so manually. We could, for example, loop over each element and set it to zero

int n = 20;

int x[n];

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

x[i] = 0;

}

Note that the array will not remember its length, so we have to keep track of this ourselves, as there is no length/size method to get the number of elements.

Initializing an array with specific elements#

We can also initialize an array with specific elements by listing them in curly brackets

int primes[] = {2, 3, 5, 7, 11};

Here, it is not necessary to specify the number of elements in the square brackets, as it is implicitly understood from the number of elements. We could, however, specify more elements if we plan on using more elements later

int primes[100] = {2, 3, 5, 7, 11};

This syntax allocates an array of 100 integers, sets the first five to the supplied values, and the remaining ones to 0.

Using arrays#

Working with arrays is like working with most sequences, and it is possible to access specific elements by index using square brackets, keeping in mind that C++ starts counting at 0. However, arrays are more low-level than Python sequences, so some more advanced operations like slicing are not available. It might also seem unusual that an array does not remember its size and that there is no built-in size operator to easily find it. However, it is possible to get the array size by computing the amount of memory required to store it via the function sizeof as follows

int primes[] = {2, 3, 5, 7, 11};

int size = sizeof(primes) / sizeof(primes[0]);

However, this syntax requires careful when arrays are passed as arguments to functions. In these cases, only a pointer (which will be discussed later) to the first element is passed, which does not necessarily take up the same amount of memory as the whole array. The best practice is then to also keep track of the size of arrays somewhere.

Example: solving an ODE#

Let us say we want to solve a coupled set of ODEs in C++ using arrays. Consider the classical physics problem in which a ball is thrown upwards perpendicular to the floor. Assuming a quadratic expression for air resistance, we have

To solve this equation, we must initialize our parameters and initial conditions

double m = 0.5;

double g = 9.81;

double D = 0.05;

double y0 = 1.0;

double v0 = 5.0;

Next we want to initialize the arrays,

double dt = 0.01;

int N = 400;

// Initialize an array of size N+1 and set the first element

double y[N + 1];

y[0] = {y0};

double v[N + 1];

v[0] = {v0};

double t[N + 1];

t[0] = {0};

And we are now ready to solve the ODE using a for-loop and the Euler-Cromer finite difference scheme:

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

{

t[i + 1] = t[i] + dt;

v[i + 1] = v[i] - (m * g + D * v[i] * abs(v[i])) * dt;

y[i + 1] = y[i] + v[i + 1] * dt;

}

This approach is very similar to how we might solve ODEs in Python using NumPy arrays. It would be convenient to store the ODE results in a file, which can be done using the following program

#include <fstream>

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

ofstream ofs{"output.txt"};

if (!ofs)

{

throw runtime_error("Unable to open file");

}

double m = 0.5;

double g = 9.81;

double D = 0.05;

double y0 = 1.0;

double v0 = 5.0;

double dt = 0.01;

int N = 400;

double y[N + 1];

y[0] = {y0};

double v[N + 1];

v[0] = {v0};

double t[N + 1];

t[0] = {0};

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

{

t[i + 1] = t[i] + dt;

v[i + 1] = v[i] - (m * g + D * v[i] * abs(v[i])) * dt;

y[i + 1] = y[i] + v[i + 1] * dt;

// Save to file

ofs << t[i + 1] << " " << v[i + 1] << " " << y[i + 1] << "\n";

}

return 0;

}

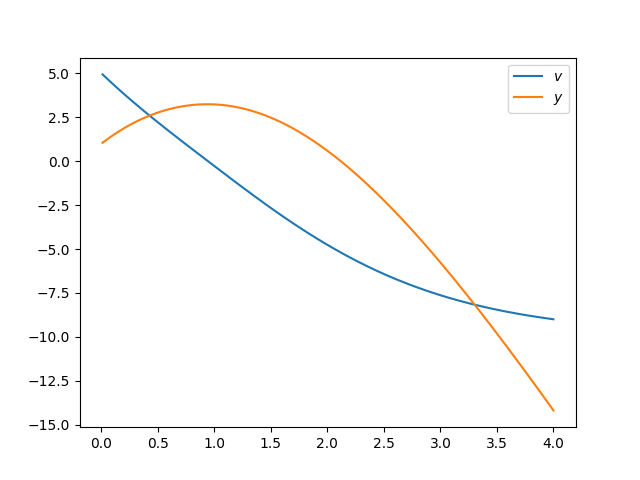

Now we can plot the results in Python

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

data = np.loadtxt("output.txt")

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(data.T[0], data.T[1], label="$v$")

ax.plot(data.T[0], data.T[2], label="$y$")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

Fig. 26 Plot from ODE solve.#

Be careful when looping over arrays#

One major benefit of using C++ is speed and low-level control. For example, running through a for loop in C++ is much faster than in Python. However, this speed comes at a cost. Consider the following code

int x[] = {2, 4, 6, 8};

int y[4];

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++)

{

y[i] = x[i] * x[i];

std::cout << y[i] << " ";

}

x = [2, 4, 6, 8]

y = [0, 0, 0, 0]

for i in range(8):

y[i] = x[i] * x[i]

Executing this in Python results in IndexError: list index out of range. This is expected because the index loops from 0 to 7, while the accessed list has only a size of 4. However, in C++, this code might run without any error. A previous run, for example, outputted the following

4 16 36 64 -1832894464 1073610756 -1311180279 -691194815

In this case, we are reading and writing to a part of memory that the program does not own. The program will most likely crash if that part of the memory is already in use by another program.

When working with C++ arrays, we do not have the safety net provided in Python, so some caution is required. Often it is better to use a vector, in which case one can use the .size() function.

vector<int> x{2, 4, 6, 8};

vector<int> y(4);

for (int i = 0; i < x.size(); i++)

{

y[i] = x[i] * x[i];

std::cout << y[i] << " ";

}

In order for the code above to function, it is important to include the vector data type.

2D arrays#

We can also make arrays with both rows and columns, which are essentially a matrix, in a similar approach

int u[100][100];

Here, u is a 2D matrix of 100 columns and 100 rows. To access elements, we now use two indices, u[i][j]. Note that the syntax u[i, j] does not work, as opposed to NumPy arrays.

Unlike Numpy arrays, these primitive C arrays are primarily for data storage and do not come with built-in linear algebra operations such as matrix multiplication - they are simply efficient ways to store data. When using C++ for matrix computations, a linear algebra package such as Armadillo might be useful to gain additional functionality.

Mutability#

Calling functions in Python: a question of mutability#

When defining a function in Python, different kinds of arguments can be given as input. However, different inputs behave differently depending on what type of variable gets sent in.

In Python, if an immutable variable is passed into a function, that variable cannot be changed by that same function as illustrated below (there are ways to do it, but in the general sense, it will not change)

x = 5

black_box(x)

print(x)

It does not matter what the function black_box is or does; the output of this code will be 5, as in the following case

def black_box(x):

x += 5

x = 5

black_box(x)

print(x)

5

If the function had changed the variable, it would have printed 10, which is not the case.

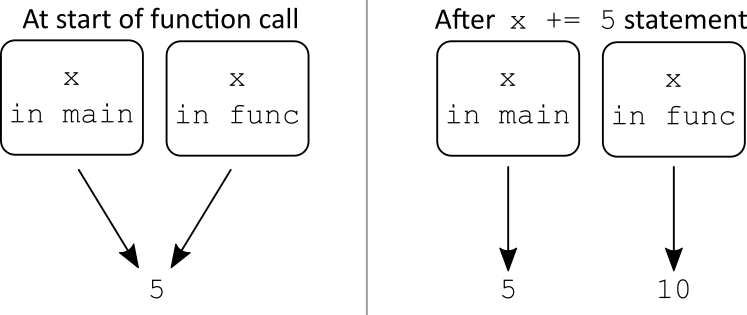

In Python, variables are references to underlying objects. And when we call the function, we have two variables referring to the same object, both called x. This can initially seem confusing, but one variable is defined in the main scope, while the other is defined inside the function. Both variables initially refer to the same underlying int object, but when we increase the function’s int object by 5 with += 5, a new int object is created behind the scenes. This is because ints are immutable objects, so the x variable from the function’s scope gets changed so that it references the new int object with a value of 10. However, the variable x in the main scope isn’t changed and still references the original, unchanged object.

Let us draw the situation:

We can go one step further in illustrating this by printing out the id of the objects. The id is a unique code each object in Python gets and which is unchanged throughout the object’s lifetime.

def black_box(x):

print("Id of x inside function before statement:", id(x))

x += 5

print("Id of x inside function after statement: ", id(x))

print("Id of x in main before call: ", id(x))

black_box(x)

print("Id of x in main after call: ", id(x))

Id of x in main before call: 139787727143280

Id of x inside function before statement: 139787727143280

Id of x inside function after statement: 139787727143440

Id of x in main after call: 139787727143280

From this, we see that the x in the main scope, i.e., outside the function, is unchanged by the function call. The x inside the function, however, first refers to the original int object but then references another int object.

Mutable objects#

For mutable variables, such as a list object, things are different.

x = [1, 2, 3]

black_box(x)

print(x)

In this case, the list may or may not be changed, as illustrated in the following example

def duplicate_list(input_list):

input_list += input_list

x = [1, 2, 3]

duplicate_list(x)

print(x)

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

So for mutable objects in Python, a function call can change the object itself. This can be useful in many cases but might lead to problems for programmers unaware of this possibility.

What is happening here is again that we have two variables that reference the same underlying object. However, when we now use +=, we are actually changing that underlying object. When the function call finishes, the outside variable will also have changed since it refers to the changed list. We can again check this using id

def duplicate_list(input_list):

print("Inside function, before: ", id(input_list))

input_list += input_list

print("Inside function, after: ", id(input_list))

x = [1, 2, 3]

print("Outside function, before:", id(x))

duplicate_list(x)

print("Outside function, after :", id(x))

Outside function, before: 139787675693184

Inside function, before: 139787675693184

Inside function, after: 139787675693184

Outside function, after : 139787675693184

As shown, there is ever only one list object.

Using mutators#

Suppose we want to make a function that sorts a list of numbers. We might want the function to produce and return a brand new list, leaving the original untouched, or we might want it to sort the original list in-place. Both of these approaches are reasonable and possible. In fact, in Python, both of these options are built-in. The built-in function sorted() returns a sorted copy of the original list, while the list method .sort() sorts the list in-place.

x = [4, 1, 0, 5, 3, 2]

y = sorted(x)

print(x)

print(y)

[4, 1, 0, 5, 3, 2]

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

x = [4, 1, 0, 5, 3, 2]

y = x.sort()

print(x)

print(y)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

None

We see that the list.sort method returns None, as it sorts the list in-place, and so does not actually return anything. Note that the in-place sorting is a list method, so we cannot use it for a tuple. This is reasonable as a tuple is immutable, not being able to be sorted in-place.

The general advice is to avoid using methods that mutate objects, especially in function calls. The function below, for example, does not mutate the input arguments

def duplicate_list(input_list):

return input_list + input_list

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = duplicate_list(x)

print(x) # x is unchanged

print(y)

[1, 2, 3]

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

Calling functions in C++#

In C++, things work slightly differently, and we are given more control over the process. The first difference is that, in C++, different data types aren’t mutable or immutable by nature. Instead, we must declare that a given object is to be immutable as we define it. By default, all objects will be mutable.

Call by Value#

We can, in C++ define the following function that changes an integer in-place.

void halve(double x)

{

x /= 2;

}

However, if we try to use this function, we notice that it does not work exactly as it would in Python:

int main()

{

double y = 10;

halve(y);

std::cout << y << std::endl;

return 0;

}

From Python knowledge, this program would be expected to output 5; after all, we have a mutable variable x that we assign to 10 and then redefine to halve its previous value. However, running this code shows that the value of y is still 10 after calling the halve function.

This example illustrates a function that uses what is called call by value. This means that when we call the function, the value of the input variable is passed to the function instead of the input variable itself. Consequently, inside the function, we have a separate variable which is a “copy” of the original variable. This happens because the variable x is first instantiated, and later its value is set equal to the input variable.

Call by value can be used for primitive data types, such as ints, and more complex ones, like vectors. If we want to define a bubble sort, for example, it can be done as follows

std::vector<int> bubble_sort(std::vector<int> numbers)

{

int temp;

bool changed = true;

while (changed)

{

changed = false;

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.size() - 1; i++)

{

if (numbers[i] > numbers[i + 1])

{

temp = numbers[i];

numbers[i] = numbers[i + 1];

numbers[i + 1] = temp;

changed = true;

}

}

}

return numbers;

}

When looking at this code, it might look like we are sorting the original input list in-place. After all, we are not creating a copy of the original list like we would need to in Python. However, because the function is a call by value, the input variable numbers inside the function is a separate variable, with values copied automatically.

This can be verified by running the following script

int main()

{

std::vector<int> original{2, 4, 3, 0, 5, 1};

std::vector<int> sorted = bubble_sort(original);

std::cout << "Original" << std::endl;

for (int e : original)

{

std::cout << e << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "Sorted" << endl;

for (int e : sorted)

{

std::cout << e << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Call by Reference#

Defining a function in C++ in the manner we have done so far yields a call by value, and it will act as explained previously. So what is the alternative to a call by value in C++? The alternative is to send in the actual variable instead of its value. This is called a call by reference, because, as the name suggests, we send as input to the function a reference to the variable itself.

To better understand this, it is important to realize that things work slightly differently in C++ than in Python. In Python, every variable is a reference to an underlying object, while in C++, some variables are objects, and other variables can be references to those variables.

When defining a function, we can use an ampersand & to specify that a variable should be a reference instead of just a value. For example

void halve(double &x)

{

x /= 2;

}

Unlike the previously defined halve function, the one above does modify the input variable. This is because the ampersand signifies that we are sending in the reference of a double variable, not just the value of one.

Note that because we use a call by reference, the function is changing variables outside of it, despite being a void function that does not explicitly return anything. In this manner, call by reference is a common way of making functions in C++ as an alternative to actually returning things.

The bubble sort example with call by reference is given in the code below.

void bubble_sort(std::vector<int> &numbers)

{

int temp;

bool changed = true;

while (changed)

{

changed = false;

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.size() - 1; i++)

{

if (numbers[i] > numbers[i + 1])

{

temp = numbers[i];

numbers[i] = numbers[i + 1];

numbers[i + 1] = temp;

changed = true;

}

}

}

}

In this version of bubble sort, we are sending in a reference of the list and not just the values. The call by reference is explicit because of the added ampersand (&) in the input. Thus we are making actual changes to the original list in-place. Because we are now sorting in-place, we do not need to return the modified list, allowing us to remove the return statement from the function and change its type to void.

Multiple variables#

Note also that a function can take in multiple variable references. We could, for example, make a function that swaps the contents of two integers

void swap(int &a, int &b)

{

int tmp = a;

a = b;

b = tmp;

}

Here we send in the references of two integer objects and swap their contents (their values). Note that we have to create a temporary integer object inside the function, as we need somewhere to store one number while copying the other. To understand this, imagine having a glass of milk and a glass of juice and wanting to swap their contents. In this case, a third glass would be necessary to temporarily store one of the contents.

This swap operation is mostly an example to illustrate what is possible, but it can also be useful in the bubble sort implementation! We leave it as an exercise to the reader to go back and improve the bubble sort in this way.

A function could also take in both call by value and call by reference variables. For example

void threshold_vector(std::vector<double> &input, double min, double max)

{

for (int i = 0; i < input.size(); i++)

{

if (input[i] < min)

{

input[i] = min;

}

else if (input[i] > max)

{

input[i] = max;

}

}

}

This function would go through a vector and threshold small and large values according to the given arguments as in the following code:

std::vector<double> numbers{2.2, 1.3, 4.8, 5.6, 1.9, 9.1, 7.2};

std::cout.precision(1);

std::cout << fixed;

for (double e : numbers)

{

std::cout << e << " ";

}

std::cout << endl;

threshold_vector(numbers, 2, 8);

for (double e : numbers)

{

std::cout << e << " ";

}

std::cout << endl;

This code gives the output

2.2 1.3 4.8 5.6 1.9 9.1 7.2 2.2 2.0 4.8 5.6 2.0 8.0 7.2

Here, the use of precision and fixed is to guarantee that each number is printed with only one decimal number. Again, we

also point out the similarity between the above C++ for-loop syntax and Python’s for e in numbers.

Small note on call by value vs. call by reference#

One of the major benefits of using a call by reference is that it avoids copying the object being used as arguments, possibly improving efficiency both in terms of speed and memory. To see why, imagine calling a function to read or modify a vector of data with millions of elements. If every time the function was called, the entire vector had to be copied, the code would use twice the required memory for this procedure and waste some additional time performing the memory copy. Instead, by just using a call by reference, the information can be read from and modified in the actual memory address.

If call by reference is more memory efficient, why not always use it? While calling by reference is efficient memory-wise, it can also lead to specific side effects and thus more easily lead to bugs. Most often, when calling a function, it is not expected that the input argument changes. Therefore, if all functions had changing variables as input, the task of finding bugs could become extremely hard. Thus calling by value is a better default, as one should need to be very explicit if one wants to break from the default conventions. Besides, copying simpler objects such as int and doubles has so little overhead it will not be noticeable. It is only for larger, more complex data structures that there is a real gain in using a call by reference.

So to summarize briefly:

Use call by value:

When functions are not expected to alter their input arguments (most of the time)

The argument is cheap to copy

Use call by reference:

When functions are expected to alter their input arguments

The arguments are expensive to copy

Use case: returning more than one thing#

Another use case of call by reference is when we want to return more than one thing. Suppose we want to define a function that loops through a vector and returns its minimum and maximum values. In Python, this can be done by finding both values and returning them as a tuple.

return min_val, max_val

However, in C++, this is not possible, as only one single variable can be returned at once. Instead, the function could be made a void function (not return anything), with references being passed for where the output variables should be stored

void min_max(std::vector<double> data, int &min_val, int &max_val)

{

...

}

Style guide: void functions#

So far, we have defined a void function every time the function changes the input argument, meaning nothing is returned. There is nothing to stop us from both returning variables and changing input arguments. However, this is considered bad style as it potentially makes the code less comprehensible for the user. If a function returns something, it will be assumed that it does not change the input variables. This convention is important to follow, as it can easily lead to bugs when sharing code and collaborating.

Some beginner programmers like to use return statements even when using call by reference. They might, for example, make a sorting function that sorts a list in-place, but also return that list at the end “for good measure”. This is unnecessary and can lead to confusion. It is best to choose whether to change the input or return something.

Is Python Call by value or Call by reference?#

A much-discussed question is whether Python is call by value or call by reference. Our intention is to show why it is actually a combination of both. When calling a function with an immutable variable, Python behaves as call by value, while if the input is mutable, it behaves more like call by reference. Most often, however, people describe Python by stating that it is call by object. There is a [great talk by Ned Batchelder discussing this topic more extensively.

Immutability in C++#

Earlier, we briefly mentioned that in C++, data types are not mutable or immutable in the same manner as in Python; instead, we can declare any variable to be immutable when we define it. To do so, one can use the keyword const, short for “constant”. The term constant is perhaps more descriptive than immutable, but the two mean the same: the object cannot change over time.

A constant integer can be defined as follows

const int MAX_ITERATIONS = 130;

After defining such a constant, we will not be able to change it. Therefore, constants should be initialized to whatever value they should have when they are utilized. Below is an example of what happens when trying to change a constant’s value

MAX_ITERATIONS++;

During compilation, an error similar to the following should be generated

error: increment of read-only variable ‘MAX_ITERATIONS’

The exact error message would depend on the user’s compiler.

Using the const keyword can, for example, be useful to define parameters or constants that will not need to be changed after compilation.

The const keyword can also be used when defining a call by reference, when passing to a function a large amount of data which requires only reading and not changing in an efficient way. An example would be the following function

double standard_deviation(std::vector<double> const &data)

{

...

}

This function takes in a vector by reference, so we avoid copying it. However, suppose we only want to calculate and return the standard deviation of the vector. In this case, we do not expect to change any of the vector’s contents, allowing us to add the const keyword to the argument input.

Note that the const keyword is not needed but was added for two important reasons. First, it makes the code more understandable; reading the function’s signature immediately informs the user that the data input is not changed, despite it being a call by reference. Secondly, it is a safeguard against bugs because trying to make a change to the vector will incur a compilation error. This is a good thing: trustworthy and reliable code should fail rather than return wrong results.

Reference Variables#

So far, we have discussed doing calls by reference. By adding the ampersand in a function signature, we denote we want to refer to a variable’s reference

void swap(int &a, int &b)

{

...

}

Note that it is possible to create reference variables outside of function definitions in the same manner

int a = 5;

int &b = a;

Here we create an integer a followed by a reference variable b, which is just a reference to a. Effectively, we have just made a new name for the initial variable in a process known as aliasing (the word “alias” means an alternative name in this context).

Notice that, just like with call by reference, changing the value of b will also change the value of a since b is a reference to a.

int a = 5;

int &b = a;

b += 1;

std::cout << "a = " << a << ", b = " << b << std::endl;

// Will output 'a = 6, b = 6'

Because a reference is just an alias for an existing variable, we cannot create a reference variable that does not refer to anything. If you just write

int &my_reference;

The compiler would protest:

error: ‘my_reference’ declared as reference but not initialized

While reference variables can be made outside function definitions, and there surely are some cases where it might be useful, this is rarely done in practice in C++. Rather, reference variables are mostly defined in function signatures. That way, they are initialized when a function is called, as seen in the call by reference examples.

Pointers#

We now turn to a different kind of variable, the pointer, which has several things in common with a reference variable. A pointer is, as the name implies, a variable that points at something.

To create a pointer variable, we add an asterisk to a data type

int *x;

In this case, x will not be an integer but a pointer variable that points to an integer. Technically speaking, it is a variable for which the value is a memory address to an integer object.

Immediately after creating a pointer variable, it will not be pointing at anything (this will be better explained later). To get it to point to something, we have to store the address of some specific integer as follows

int *x;

int a;

x = &a

Here the final statement sets the value of the pointer (x) to be equal to the integer variable. Note that we use the ampersand (&) to find the address of a variable. The ampersand is sometimes referred to as the “address-of” operator for this reason. From this syntax, due to the use of the ampersand, we can see that the pointer stores a reference to a.

At this point, it might feel unclear what the difference between a pointer and a reference is. This confusion is to be expected, as these concepts are very abstract and similar, being considered one of the most subtle parts of C++ for beginners to understand.

Pointer vs. reference variable#

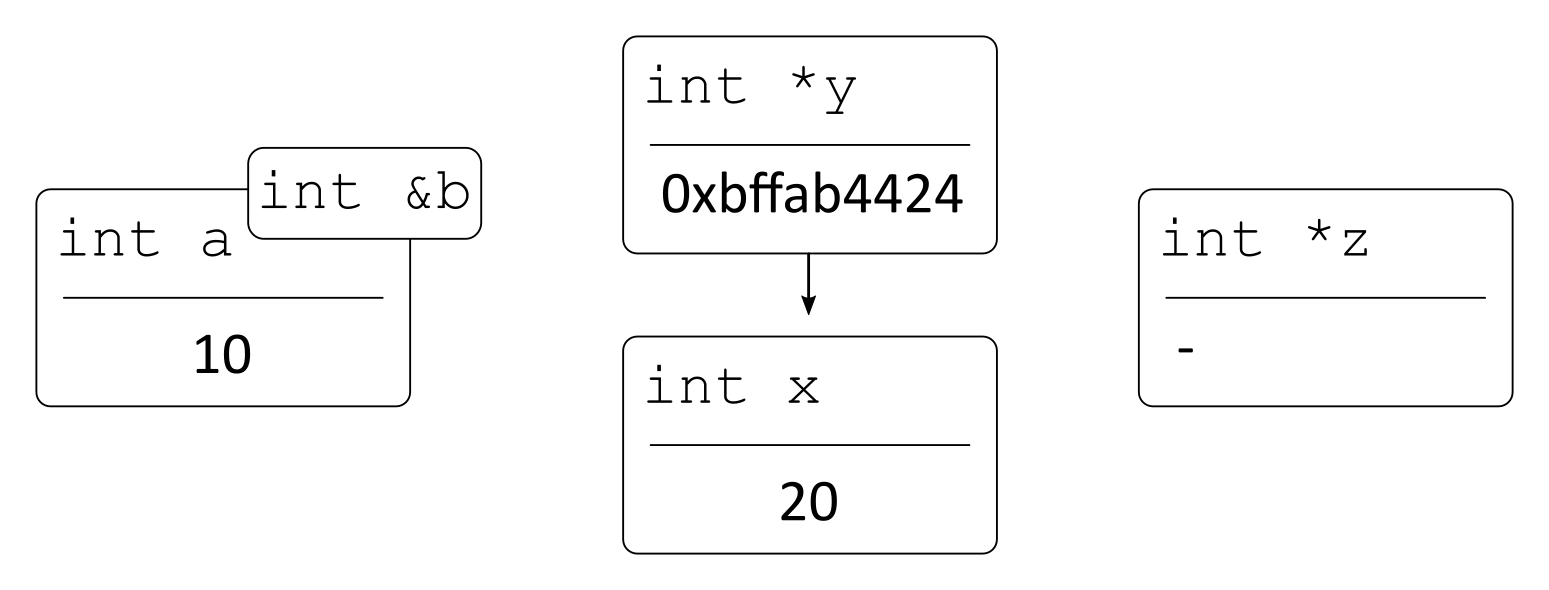

To elucidate the discussion, let us create some different variables

int a = 10;

int &b = a;

int x = 20;

int *y = &x;

int *z;

Here, a is an integer variable and b a reference variable to a. Similarly, x is an integer, and y is an integer pointer, pointing at the address of x.

Whereas b is just an alias, or alternative name, for a, the pointer y is a variable in its own right, containing a value with the address to x. For one, we can create a pointer variable that does not point at anything, as is the case of z. Recall that this is not possible for references.

Fig. 27 A reference variable is an alias for another variable, while a pointer is a variable that stores a memory address as a value, and can thus point at something.#

Because a reference is just an alias, we can use a reference variable as though it was the actual object we want to change. One example of this is the following

b += 5;

Which would change a. We can verify this by printing out both a and b:

std::cout << a << std::endl;

std::cout << b << std::endl;

And we see both have become 15.

For the pointer variable, however, y refers to the pointer variable itself.

y += 5;

The above code then changes the pointer variable and not the variable points to. Printing both x and y now gives the following

std::cout << x << std::endl;

std::cout << y << std::endl;

Result:

20

0x7ffc4258e59c

We see that trying to change y directly does not impact x. Furthermore, trying to print out y directly gives the pointer value, i.e., the address, instead of the integer it is pointing at.

The major point we are trying to get to is that a reference variable is a simple alias/additional name for an object, which is useful when defining and using functions with a call by reference. Pointers, on the other hand, are variables in themselves, with their own value, being able to exist without anything to point at.

The Dereference Operation#

Since we cannot use a pointer to directly affect the variable it points at, the reader might be questioning its utility. While we cannot use pointers to directly affect the variables they point at, we can use the dereference operator as follows

*y += 10 : std::cout << x << std::endl;

std::cout << *y << std::endl;

By putting an asterisk (*) before a pointer variable, we dereference the pointer and can interact with whatever it is pointing at. The term itself is perhaps not very well named, but remember that the pointer and the pointee are two different things! For the dereference operator to work properly, a pointer needs to know what kind of data it is pointing at, which is why we have to create an integer pointer or a vector pointer, and so on. Although it will become clear later, the reason for this requirement is related to the fact that the values of an array are stored contiguously in memory, meaning that the memory addresses for x[i+1] will be next to the memory address of x[i].

Here is a table summarizing the concepts so far.

Syntax |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

integer variable |

|

reference variable |

|

pointer variable |

|

get address of i |

|

content of address/pointer |

Null-pointers#

So far, we have stated several times that a pointer does not need to point at something. Let us justify this statement.

Suppose we define an integer or a double but do not initialize them to any value

int x;

double y;

The above statement allocates memory to store the variables, giving them a piece of memory that has to be in some state, meaning these variables have to have some value; they cannot just be “empty”. In C++, the value of these will effectively be random unless specified.

Similarly, pointers are variables that store a memory address, and when they are defined, a memory address is allocated for storing them. Therefore, as with the other variables, the pointer has to have some value. To be precise, when we say the pointer does not point at anything, we do not mean it does not have any value; instead, it has the value “null”.

In this context, null is a value reserved to mean “pointing at nothing”. By pointing our pointers at null, we are telling the compiler (and ourselves) that the pointer is not pointing at anything.

Before C++11, it was common to refer to null as NULL. A pointer could then be reset as follows

int *x = &a;

x = NULL;

After C++11, this still works. However, using the nullptr is a more modern way to achieve the same result

int *x = &a;

x = nullptr;

We can check whether a pointer is pointing at an actual object with a simple if-test

if (x == nullptr)

{

...

}

A comment on style#

So far, we have defined reference and pointer variables by putting special characters next to the variable name, like

int *x vector<int> &primes

However, as usual, the whitespace is arbitrary, so we could just as well have written

int* x std::vector<int>& primes

Some people prefer the latter as it looks like the character is referring to the data type. The downside to this is that it requires attention when defining multiple variables in one line. In C++, multiple variables can be defined in one line as below

int i, j, k;

which is equivalent to

int i;

int j;

int k;

However, if one of the variables in a pointer in the one-line definition,

int *p, q, r

only p would be a pointer, while q and r would be normal integers. However, this is made more explicit by writing

int q, r, *p

Details like this are one reason why many style guides state that combining multiple definitions in one line should be avoided. It would be more explicit to just split definitions over multiple lines.

Lastly, some prefer to put a space on both sides of the special character

int * x std::vector<int> & primes

The most important point is to be consistent with whatever style is chosen.

Call by pointers#

We started by discussing call by reference using reference variables, but the same result can be obtained by using pointers

void swap(int *a, int *b)

{

int temp;

temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

Note that we need to refer to *a and *b to actually use the variables (dereference). Similarly, when calling this function, we need to send in actual integer pointers or the address of integer variables (which can be obtained with the address-of operator)

int a = 100;

int b = 300;

swap(&a, &b);

Some refer to this as doing call by pointers, but most just consider this a type of call by reference.

Using pointers over references in a function call might seem like a lot of additional boilerplate compared to just using reference variables and, in many cases, it might be. Nonetheless, when already working with pointers, using call by pointers makes more sense.