Course Summary#

This lecture marks the end of IN1910, and as such, will mostly be a summary of the topics we have gone through during the semester. We will also try to offer a big picture view of scientific programming, and give some helpful advice along the way.

The Goal of IN1910#

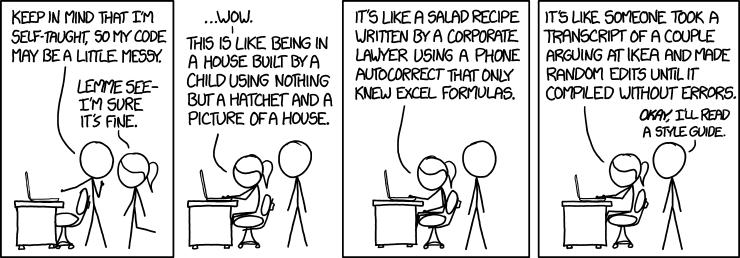

We can start of by repeating what we started the whole course with: the goals of the course itself. The name of the course is Programming with Scientific Applications, and so the goal is to focus on the type of programming scientists use as a tool in their everyday life. This is a tool many scientists have not been formally trained in, but are rather self-taught, occasionally leading to inefficient coding and bad practices. The movement Software Carpentry is trying to rectify this situation somewhat, by giving workshops in good scientific programming.

Our goal in IN1910 has not only to teach you programming itself, but also important tools and techniques for developing code more efficiently, and in a way that produces reliable and understandable code.

Major Topics of IN1910#

Let us quickly go through the main topics we have been through in this course and say a few words about each.

Object Oriented Programming#

The biggest topic of IN1910 is object-oriented programming. Not only did we devote many weeks at the start of the course to OOP basics, but it has been a recurring theme also in the other parts of the course.

Object-oriented programming is a programming paradigm where we break down and solve problems by defining objects and how they interact. The major benefit of OOP is that good use of it can lead to elegant programs that are easy to understand and work with.

Also recall the four pillars of object-oriented programming:

Abstraction

Encapsulation

Inheritance

Polymorphism

Classes in Python#

Throughout the course, you have gotten a lot of exercise in defining and using your own classes in Python. Hopefully this has made you more comfortable in the use of classes as a good technique for developing and organizing your code.

To make really elegant and handy classes, the trick is often to define the special methods we keep returning to. The major ones we keep using in this course are __init__, and __call__, but we have also seen other examples such as __add__, __repr__, and many more. We have also extensively used the @property decorator to easily implement properties for our class that are more advanced than simple data fields.

There are tons more which we have not covered in this course. The main take away is that it is you, as the developer, who decides how your custom objects should behave, and you can do this for nearly any aspect of your code by implementing good special methods.

Classes in C++#

You have also gotten experience with implementing classes in C++. Recall that C++ is often referred to as “C with Classes”, and object-oriented programming is one of the major differences between C and C++.

You have seen how you can implement structs and classes in C++, and how things are both quite similar to Python, but also quite different. For one, we can overload operators in C++, in much the same way as special methods work in Python. Unlike Python however, C++ has implicit self-reference, and actually private variables and methods.

Programming in C++#

Speaking of C++, this has been a second major topic of the course, devoting four full weeks and a project to purely C++.

Our main goal hsa not been to make you experts at C++, that is not possible to do in a year, much less four weeks. Rather, our goals have been to:

Make you familiar with a C-style language#

Recall that C is the most used programming language ever. It was, and still is, so ubiquitous, that many other languages has borrowed much of their syntax from C. This is true for C++, C#, Java, and many others. Because C, and its descendants are so popular and common, chances are that you will need to work with one of them later on in your studies or future career. This is true both for scientific programming, or if you move into other careers where you use programming. By knowing one C-style language, you are much better suited to reading and understanding code in these other C-style language, because their code is so familiar. For instance, while you might never have written a line of Java code in your life, this Java example will most likely look very familiar:

public static int factorial(int n) {

int total = 1;

for (int i=1; i<=n; i++) {

total *= i;

}

return total;

}

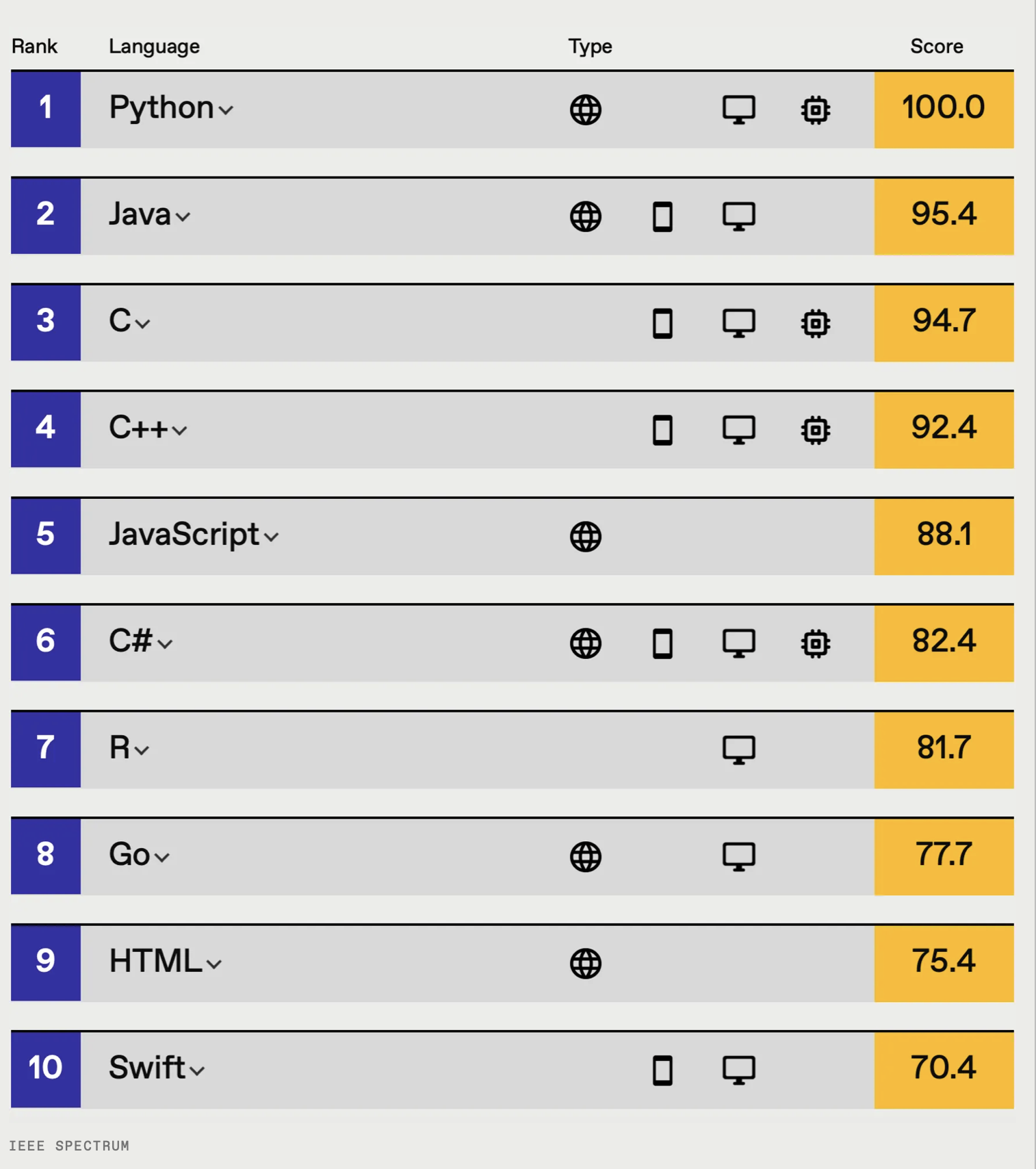

To show how helpful knowing a C-style language can be, let’s take a quick look again at the IEEE Spectrum Ranking for 2018, which tries to rank programming languages by popularity, i.e., how much use they see. We can see that Python is number one, this is probably because Python is high-level language it is quick to prototype in. The next four languages in the list however, are all C-style languages. Knowing Python and some C++ therefore goes a long way.

Give you an understanding between the differences between Python and C++#

Another important aspect of teaching you some C++, is to give you a better understanding of Python, by showing you how Python differs from a language like C++. Even if you going forward more or less work solely in Python, we believe knowing some C++ will make you a better programmer.

The biggest difference between C++ and Python is that C++ is a low-level language, while Python is a high-level language. This means that C++ code lies closer to machine code, while Python code contains more abstraction. This reflects in most of the differences between the languages. The major benefit of a low-level language is that it can give very fast code, if programmed correctly. This is also true for C++, as it can become much faster than Python code. While the main benefit of a high-level language is that it is often easier and faster to develop code, and the code can usually be shorter overall and more readable.

Other differences we have gone through are that C++ is a compiled language, while Python is an interpreted language. C++ is statically typed, while Python is dynamically typed. Python has automatic garbage collection, whereas C++ does not. C++ supports pointers and specific memory management, whereas Python does not.

All of these differences sum to two programming languages that are good at different tasks, and should be used in different ways. C++ is fast, and good at handling heavy computations and simulations. Python is good for more or less everything else, and is perfect for quick scripting and prototyping, data analysis, data visualization and so on. This categorization is however, perhaps a bit too simple, and personal preference is also not to be understated.

The Need for Speed#

Put simply, C++ is much faster than Python, if programmed correctly. This is a major reason C/C++ are so much used in scientific programming, which often requires heavy computations. However, as we have seen in the last portion of the course, writing pure C++ code is often not necessary. It might be sufficient to write only the really slow parts in C++, and then use it from Python. This is the way NumPy is built, and so for example, one can make efficient Python programs using numpy, because the slow parts of the code are running in pre-compiled C code. Similarity, we might get away with just-in-time compiling our Python code into auto-generated C or C++ code using tools like Cython or Numba. Knowing C++ will make using these techniques and tools much easier.

Data Structures and Algorithms#

The next topic we moved into was data structures and algorithms, a big field in informatics.

Data structures are how we organized the data of our programs in memory, and it is what underlies our data types. We have looked at four different data structures in IN1910:

Arrays

Dynamic Arrays, aka, Array Lists

Linked Lists, both singly linked, doubly linked and circularly linked

Binary Search Trees

These are just some possible data structures, but are usually considered the “classics”. Other classics are heaps, stacks, hash maps and so on. However, the list of data structures and their use cases is near endless.

While we have focused a lot on implementing our own data structures, this is rarely required in practice, as most common data types are either built-in, or available through standard libraries. However, by implementing them ourselves, we have hopefully gotten a better understanding of what data structures actually are, and how choosing the right data structure of the right problem can be crucial.

We have also compared the performance of our data structures, and look at other algorithms, using algorithm analysis. Here we have focused mostly on Big-Oh analysis, which is mostly concerned with classifying how algorithms scale. Big-Oh is an important tool when analyzing problems and algorithms to solve them.

Generating Random Numbers and Stochastic Simulations#

We have looked at how random number generators work, and how we can produce pseudorandom numbers on a computer. These are numbers that are produced in a completely deterministic fashion on a computer, but whose statistically properties are sufficient for scientific experiments and studies.

The two major benefits of pseudorandom number generation is that (1) the process is extremely fast, much faster than generating true random numbers and reading them in. And (2) because the algorithm is deterministic, we can seed the random number generators. This allows us to reproduce the same sequence of statistical randomness. This is extremely useful, because it means we can make reproducible experiments, and it is also helpful when testing, developing and benchmarking code.

In practice, we have learned that the gold-standard of random number generators is the Mersenne Twister algorithm. Although this probably won’t be true for all eternity, so make sure to keep up to date with what a good, and suitable, pRNG for your use case is! Luckily, Mersenne Twister is ubiquitous, and available in nearly any programming language. It is for example the engine Python uses by default, and it is also available in C++ through the random standard header.

Using our random numbers, we have looked at some simple types of stochastic simulation, such as random walks and chaos games. This has hopefully given you some insight into how we can use randomness to model stochastic phenomenon, and a little about how such systems can be analyzed and understood.

Optimization#

The final major topic we went through was optimizing and speeding up code. Here we first took some time to understand that there is a place and a time for optimization. Once should generally try to implement a working solution that is well tested and organized, before one starts trying to speed it up. This was summarized in the three steps:

First make it work

Then make it elegant

Then make it fast

When getting to the last step, we want to change things in our code to make it faster. This topic is hard to cover in a general sense, because speeding up an implementation is very problem-dependent. However, a general rule is to not just try to optimize everything, but to identify the bottlenecks, i.e., the slow parts of your program. These parts can be identified using a profiling tool. In Python we have look at two such tools: cProfile and line_profiler. Recall the 90-10 rule: more than 90% of the runtime of a program is usually spent on less than 10% of the code, and it is those 10% we should focus on. Sometimes the numbers are even more skewed, and we should really focus only a few lines of the code.

When optimizing, it is important to get a good handle on how fast the code actually is, and this we can do through timing experiments and benchmarks. In Python we did this with the package timeit, which is very practical to use in Jupyter.

When optimizing code itself, we can look for better algorithms to solve our problem in other ways, or we can look for clever tricks to get around slow parts of our computations or ways to do less work. Sometimes however, doing less work doesn’t seem to be an option. To speed things then, we should look to run the slow parts of our code in a lower-level language. In Python, this can be done through using libraries such as numpy and scipy, which runs pre-compiled C code in the background. Or we can use tools like Cython and numba to just-in-time compile our own code to make it faster.

Tools in IN1910#

In addition to the topics we have gone through, we have spent plenty of time covering useful tools, techniques and best practices as well. Let us quickly go through the most important ones.

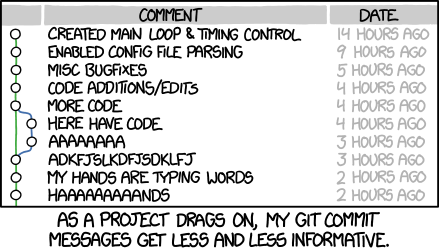

Version Control with Git#

Perhaps the most important tool we have covered in IN1910, although it might not feel like it, is version control. In this course you have used git to carry out your project work and collaborate in different ways. This is a hugely important skill to have when working on larger software projects. Version control makes your life much easier in the long run, and tools like git are more or less universally used.

Fig. 68 XKCD #1597#

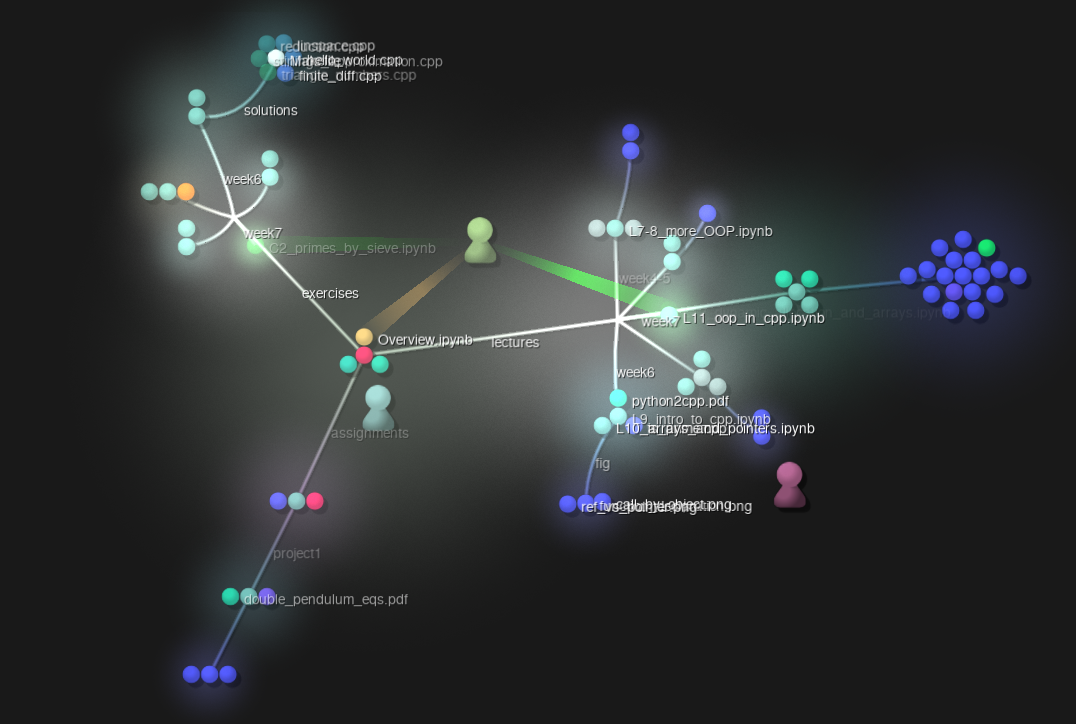

Here we can also mention a cool tool which we have not covered in IN1910, for visualizing a git repository. Many such tools exist, and they can sometimes be helpful with understanding a large project or its history. Or it can simply be used to create cool graphics. One such tool is gource. If you are on Windows, you can download an .exe from the website, otherwise you can install through apt:

sudo apt-get install gource

Now you can run gource from inside a git repo to create a visualization of the repo over time:

cd IN1910

gource

Now you get up an animation that shows how files are created and changed over time by different people. The visualization will look cooler for larger project with many people working on them. You might not have many such repositories yet, but you can try to run one of your project repositories through gource, or the IN1910 course repository itself.

Fig. 69 A snapshot of an animation of the IN1910 repository visualized with gource#

Unit Testing with pytest#

We have covered the importance of testing your code and have covered especially the package pytest for Python, which makes defining and running tests easier. This can allow us to automate the process of testing our code, which is crucial to producing high-quality and reliable code. Although we have not covered it in detail, running unit tests after each commit can be a real quality assurance for large and long software projects.

Improving Code Style with Style Guides#

We have discussed how important it is to have a good and consistent code style. What constitutes a good style will always be partially subjective, but the end goal is to produce code that is readable, understandable and structured.

In Python we have recommended that you follow the style guide PEP8. While this is not the only Python style guide out there, it is the most used, and following it will give you code that is organized and neat. However, the main goal is not to force you to follow a specific style, but to show you that following a consistent style is important.

Writing Documentation with docstrings#

While we did not cover any specific tools for working with docstrings, we have covered why docstrings are useful, and how they should be written. Here, especially PEP257 is of especial importance, as it describes normal conventions for Python docstrings, which will make it easier for you to know what is supposed to be in your docstrings. And for other people to understand your code and your docstrings.

Timing Experiments and Profiling#

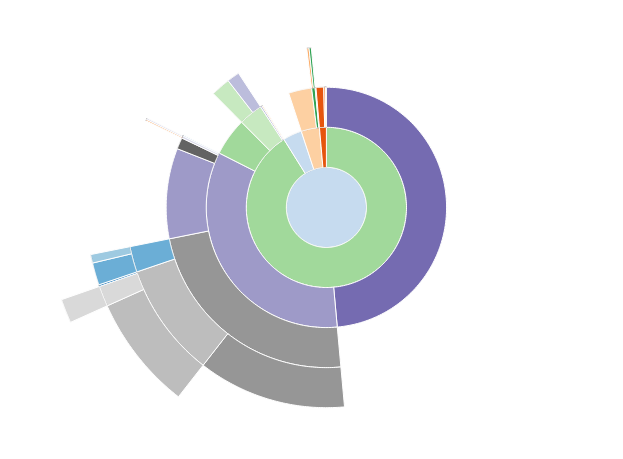

We have looked at the package timeit to do timing experiments, and cProfile and line_profiler to do profiling of code. These tools are important to use if we want to optimize code in a structured, organized and efficient manner. These are however by no means the only ones. Another popular profiling tool is snakeviz. Instead of just writing out the results in a table, snakeviz profiles the code and shows it in a HTML-based interactive 2D graphic called a sunburst.

JIT Compiling with Cython and numba#

While we have not taken the time to cover either in detail, we have looked at how we can just-in-time compile Python to more efficient and faster code using two tool: Cython and numba. Both provide tools for automatic JIT compiling, but will do an even better job if we know what we are doing and we can help them along the way.

The SciPy Stack/Ecosystem#

Lastly, while we have not explicitly mentioned it, we have worked our way through large parts of the SciPy Stack. SciPy stands for Scientific Python, and is also the name of a Python library, which we used for Project 1.

While scipy is a library, the name is also used to refer to a larger community developing commonly used tools for scientific python, this includes for example numpy (numerical python), and sympy (symbolic python).

A lot of these libraries for scientific programming were collected in something referred to as the [SciPy Stack], which is officially the libraries:

NumPy, for efficient array computations

SciPy, a collection of algorithms and domain-specific tool-boxes

Matplotlib, a package for high quality 2D plotting, and basic 3D plotting

IPython, an interactive python shell useful for fast testing and data analysis

pandas, a library for data analysis and statistics

SymPy, a library for symbolic math

Of these, we have extensively used most of them, with exception of pandas and SymPy. We have used IPython through Jupyter notebooks, which were previously known as IPython notebooks.

The Scipy stack definition has been deprecated, as it is no longer seen as useful. Instead people sometimes refer to the SciPy ecosystem, which encompasses the entire SciPy stack, but even more useful tools, like Cython and Jupyter.

Put simply, the SciPy ecosystem encompasses many packages that can be crucial and important if you are working with scientific programming in Python. Three packages we have not covered, but which can be helpful for specific tasks are:

scikit-learn, a package for efficient data fitting and machine learning

scikit-image, a package for efficient digital image analysis and manipulation

h5py, a package for reading and writing files in the hdf5 binary file format, which is becoming more and more common for storing large amounts of scientific data.

Best Practices#

In addition to the major programming topics and the important tools we have covered in IN1910, we wanted to leave you engrained with some good practices for scientific programming. In fact, ideally we would want you to walk away with some best practices.

It can be hard to narrow down exactly what is the best practices of scientific computing, as asking different people will most likely net you different answers. The main goals however, should be to program in a way that:

Gives reliable code that produces trustworthy and reproducible results

Give understandable and organized code that is easy to work with, maintain and build on

To make both development and running of code as efficient as possible, without sacrificing quality

The 2014 paper Best Practices for Scientific Computing by Wilson, et al, discusses the need for better practices in the field of scientific computing. They have gone through and identified what they believe are 8 majorly important points to focus on for scientific programming.

We will now try to go through each of these 8 “rules”, one by one, and explain briefly how they relate to IN1910. Hopefully much of these points have been covered, but perhaps some will sound new. For each rule there are a number of sub-rules, or advice.

Rule 1) Write Programs for people, not computers#

The first point emphasizes what we have referred to as readability of code. While a program is written to solve a given task, we should not focus solely on solving the task at hand, as this might lead to complicated and hard to read code.

By keeping your code structured and understandable while developing new software, you make it much easier to read and understand the code for both yourself and others. This will make it easier to catch and fix bugs in the code, improve it or extend it, and is also very useful if you want to optimize your code.

When writing a code that is structured and understandable, keep in mind that the human mind can only think of so many things at once, and if things become too complicated, it will be hard to understand how different aspects connect together. Therefore:

1a) A program should not require its readers to hold more than a handful of facts in memory at once

Here, Wilson et al is not referring to keeping things in computer memory, but in human memory. As a program grows in size it starts getting harder to keep the big picture understanding, and so the program needs to be organized in a hierarchical manner. The best way to accomplish this is often to divide a program into small functions or methods that perform a single, well defined, task.

This point is also strongly connected to object-oriented programming, as one of the main benefits of OOP is that it makes this step easier to accomplish in practice. Basically all 4 pillars of object-oriented programming can be connected to this rule.

Fig. 70 Comic explained: The “goto” keyword is an old keyword available in most programming languages, that works a bit like a function call that never returns, we simply jump somewhere different in the code based on line numbers or a function name. The use of “goto“‘s have always been quite controversial, as they are considered to usually lead to less readable code that is hard to debug. Luckily, for this reason they have become unpopular. XKCD #292#

1b) Make names consistent, distinctive and meaningful

This point is hopefully quite self-explanatory, but good variable names is crucial for readability. From the PEP8 style guide we have also learnt that we should ideally choose variable names differently based on what kind of variable we are dealing with.

1c) Make code style and Formatting Consistent

The points underlines what we have been saying: code style is important. The best way to ensure consistent style is to decide on a style guide to follow, or to make one for yourself.

Fig. 71 XKCD #1513#

Rule 2) Let the computer do the work#

This is a point we have admittedly not covered in great detail in the course. It is connected to finding efficient workflows, and using a computer as a tool to speed up common tasks. This can for example be connected to writing simple scripts in Python or bash to automate simple tasks.

2a) Make the computer repeat tasks

2b) Save recent commands in a file for re-use

2c) Use a build tool to automate workflows

We have briefly mentioned the build tools mentioned in point (2c) in IN1910, but have not gone into details. These are tools that automatically re-compiles and reruns our code when we change it, verifying that it works correctly and perhaps updating our results. These tools can also be referred to as continuous integration tools, and are useful to integrate with version control. Good tools here can be Travis CI or Snakemake, but many others exists. Which to choose largely depends on your use cases and preferences.

If you want to learn more about practical automation and making efficient workflows, the course IN3110 might be a good option.

Rule 3) Make incremental changes#

When solving a new problem, it is important to work in small steps. This is to keep things manageable, and to ensure that the code itself becomes structured and understandable. After solving a small part of a large problem, ensuring that it works with testing and restructuring it is a good idea before continuing.

3a) Work in small steps with frequent feedback and course correction

When working in a team, working incrementally also means having frequent meetings and feedback from each other. However, this point is still important when working alone, as “feedback” can also come from writing tests or example use cases, as you can get a feel for what works well, and what might need to be restructured or changed.

3b) Use a version control system

This part is very important, and we have covered it in detail in IN1910 through the use of Git.

It is important to also work incrementally on Git, meaning you should commit regularly, with good commit messages.

Fig. 72 XKCD #1296#

3c) Put everything that has been created manually in version control

We should put everything we create into version control, so that we have a back-up and a revision history. However, things that are not manually created, but come for automatic process, such as compiling a source code, configuration files made by editors, results from running a program etc, might be useful to keep out of the git repository to keep things tidy and neat. The best tool to do this is to make a good .gitignore file. Recall that the website gitignore.io can be a good resource here.

Rule 4) Don’t repeat yourself (or others)#

4a) Every piece of data must have a single authoritative representation in the system

4b) Modularize code rather than copying and pasting

4c) Re-use code, instead of rewrite it

The DRY principle is crucial in programming. Not only is it important to efficiently develop code, but it can also be important for readability and maintenance. This is because if a code has “code clones”, i.e., the same code doing the exact same thing multiple places, we quickly end up in situations where we think we fixed a bug, but we only fixed it in one location, and so the bug is still present. Or perhaps we go to modify the code, but do it only in one of multiple locations, leading to new bugs. Having the same code multiple places can also be a sign of unorganized and hard to understand code.

If you end up with situations where you feel you need to clone your code, try to look for ways to instead reorganize it and modularize it. Perhaps you can implement a general function that does the task, with special parameters to control the behavior. Or perhaps making a class, or using inheritance, is a better way to organize and structure your code?

Another important point: while studying, writing your own code from the ground up is perhaps the best way to learn. In practice however, most simple, general problems, such as solving ODEs or matrix-matrix multiplication, have probably been extensively looked at in software available out there. When working on actual projects, and the end goal is simply to have a working code, there is no need to reinvent the wheel.

On a humorous note, because DRY is such a well-known phrase, some also refer to the “WET” principle. This isn’t really a thing, but it would be the opposite of DRY. As a tongue-in-cheek, several acronyms for what WET should stand for have been proposed:

“We Enjoy Typing”

“Write Everything Twice”

“Waste Everyone’s Time”

While these are meant mostly for humour, they do quite accurately point out that not following DRY is very inefficient.

Rule 5) Plan for mistakes#

Planning for mistakes is crucial. Nobody is perfect, and we will make mistakes. We have discussed this multiple times in IN1910, especially so when discussing how to write reliable code.

5a) Add assertions to programs to check their operations

Recall that assertions are safety-checks we can put into a code to ensure that certain conditions are actually true. These can be important, because a reliable program should fail rather than return the wrong results. An assertion is a good way to halt a program’s execution if something goes awry, making it more trustworthy, but also easier to fix. Using extensive assertions can be referred to as defensive programming.

An alternative to assertions is raising errors, which we have also discussed. By raising errors when input is wrong, or something is off, is a good alternative to assertions that can also inform the users of what is wrong. Here, defining your own custom errors can also be a good idea.

5b) Use an off-the-shelf unit testing library

Using an off-the-shelf testing library instead of making everything from scratch is a good idea. For one it is more efficient, as we can both develop and run tests more easily. But it is also helpful when sharing code, as it will be easier for other people to test your code as well.

5c) Turn bugs into test cases

This is the process of regression testing which we have discussed. When you find a bug in an important software, that bug should become a new unit test. This ensures that the bug remains fixed, and is never reintroduced at a later time.

5d) Use a symbolic debugger

We have not covered this point in IN1910 sadly, mostly due to time. A debugger is a tool that helps us find bugs in a program by allowing us to execute the program line by line and seeing how variables are created and changed over time. Such tools can make development and fixing bugs much faster. The term “symbolic” debugger doesn’t really mean that it is a graphical tool, but rather that it understands variable names. Most modern debuggers are symbolic, and all Python debuggers are.

If you want to read about debuggers on your own, you can read about the package pdb (Python Debugger), or you can use IPython embed to run a script, but halt at a crucial moment and open the code in an IPython shell, allowing you to explore variables or test out hypotheses.

Rule 6) Optimize software only after it works correctly#

We have tried to emphasize this point strongly in IN1910. First make it work, then make it elegant, then make it fast.

6a) Use a profiler to identify bottlenecks

Profiling code is crucial, so that we know what parts are actually slow and needs to improve

6b) Write code in the highest language possible

Writing code in a high-level language like Python has many benefits, and the only major drawback is the speed. If our Python code is too slow, we shouldn’t give up on the entire code, we could perhaps use Mixed programming to only move the slower parts over into something like C++. Here tools like Cython and numba are useful.

Rule 7) Document design and purpose, not mechanics#

7a) Document interfaces and reasons, not implementations

7b) Refactor code in preference to explaining how it works

7c) Embed the documentation for a piece of software in that software

Rule 8) Collaborate#

Use pre-merge code reviews

Use pair programming when bringing someone new up to speed and when tackling particularly tricky problems

Use an issue tracking tool

Where to go from here?#

We hope you have learned a lot from IN1910, and have become all around better programmers that feel more comfortable and certain in your role as scientific programmers. Of course, it is obvious that we cannot cover everything in a single, fairly introductory, course. If you want to learn even more about scientific programming, there are plenty of options to choose from. Let us present a small selection of them

IN2010 — Algorithms and Data Structures

This course starts where we left of, with implementing some simple data structures and analysing them and their behavior. IN2010 however, goes much further, present plenty of different data structures. In addition, you learn more about algorithm analysis, and also learn about graph algorithms. This course is a very fundamental course if you want to grow as a programmer.

IN3110 — Higher Level Programming

This is a Python course that focuses more on using Python as a scripting language. In addition to using Python, you will also learn some bash scripting. The course will also go more into package python programs, data analysis with pandas, making webpages with flask and machine-learning with Scikit-Learn.

IN3200 — High-Performance Computing and Numerical Projects

This is the course to take if you want to learn more about optimization and making really fast code. Here you will learn about making high-performance code and more about parallelization.

INF2310 – Digital image analysis

A course on how 2D digital images are represented and stored on the computer, and how we can manipulate it through filters and similar. Digital image analysis is an interesting topic, and depending on what field you are most interested, it could perhaps be very relevant for you.

FYS3150 – Computational Physics

A project based course in C++ based on specific examples from the field of physics. While this course is definitely more relevant for physicists, it can be a good course to take from anyone who wants to learn more about the use of C++ for scientific computing, as it is very hands-on.

(Master level) IN5270 – Numerical Method for Partial Differential Equations

If you want to learn more about numerically solving partial differential equations, this is probably the best course to take, although it is at the masters level. This course covers both finite difference methods, but also finite element methods, a highly efficient and much used method for solving PDEs.