Introduction to Object-Oriented Programming#

This section will look at object-oriented programming (OOP for short). This is one of the major components of IN1910. We will look at what OOP is and how to program object-oriented in Python. In later chapters, we will cover some more theory of object-oriented programming and touch on object-oriented programming in C++.

What is Object-Oriented Programming?#

Object-oriented programming is a programming paradigm. Simply put, a paradigm is a way to think about, organize, and write code. Paradigms are used to classify and describe languages and programming styles. Many other paradigms exist; some examples are procedural, functional, imperative, and symbolic programming. Most programming languages do not belong to a single, specific paradigm. Instead, most languages, including Python and C++, are described as multi-paradigm, meaning it is possible to structure and write code in multiple paradigms.

Object-oriented programming is a way of solving problems, or building software, by defining data as objects, and specifying how those objects behave and interact. It is one of the most popular programming paradigms and is often used when developing software. When done correctly, OOP leads to code that is usually relatively easy to understand, use and extend.

The origins of OOP#

Ole-Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard invented object-oriented programming in Norway in 1967. They made a new programming language called Simula, the first object-oriented language. While Simula was revolutionary and historically an important language, it did not see widespread adoption. Inspired by Simula, the language Smalltalk came on the scene in 1972 and saw a broader use, pushing the use of OOP. Smalltalk still sees some use today, mainly as a means of teaching OOP and introductory programming. In 1983 C++ arrived on the scene, which can be described as the first “industrial” object-oriented language. C++ was invented by Bjarne Stroustrup. He thought Simula had some interesting features for extensive software development but considered it too slow to be practical. Therefore, he started developing “C with classes”, which would eventually become C++.

Fig. 7 You might have thought the “ostehøvel” was the greatest Norwegian invention, but Simula is where it’s at#

What are objects?#

So what are objects? In Python, all variables are objects. In a sense, an object is similar to a variable. All objects have a few characteristics we can associate with them:

All objects have a given object type. We, for example, have integers, strings, lists and dictionaries. Objects of these types will behave differently, but they are all examples of objects.

Objects behave in specific pre-defined ways. We can, for example, perform arithmetic with numbers, sort lists, or split a string. The type defines what actions we can and cannot perform. For example, it would not make sense to divide a list by another.

Objects typically have information or data stored in them. For integers and floats, this would be their numerical value. For a list, it is all the elements in the list.

One of the reasons OOP is so popular is that it is pretty intuitive because it mirrors real life. We tend to divide everything into specific concepts or objects when we think or talk to make sense of the world around us. Cars are objects, and so are buildings. People are objects, too, in the software sense. It is not only physical things that are objects, either. A given calendar date is an object defined by its day, month and year. This course is IN1910, which could be described as an abstract object. We can think of a job as an object. In this sense, an object is a data abstraction that attempts to capture some important property or feature.

Everything in Python is objects. We are often defining and using objects without thinking about them. Does this mean we are programming object-oriented? Not necessarily. As mentioned in the introduction, the important thing is thinking and solving problems in an object-oriented manner. To code OOP properly, one should ask what kind of objects are best for organizing a program and solving problems. Probably the most important task of programming object-oriented is to define new data types and how objects of that type should interact and be represented.

Example: A contact list#

Think about the contact list on a smartphone. For each contact, one can store information of different types: name, multiple phone numbers and emails. Some contacts may have many pieces of information, while other contacts only have a single piece of information.

Let us say we want to implement such a contact list for a new phone system we are making. We might start thinking about how to solve this problem. It makes sense to think of each contact as an individual object. Each piece of information belongs to a given contact, so it should be part of that object in the code.

To begin with, we only want to store information about each contact, so dictionaries would be a natural choice. We can use key-value pairs to store the information we want and ignore the pieces of information we do not want. Other parts of the software system can then go in and access information from the contact dictionary as needed

contact = {"name": "Lisa", "email": "lisa@python.org", "mobile_number": "767828292"}

print(contact["email"])

lisa@python.org

However, our dictionary can only store information on the contact, and we cannot add new functionality. A more general way to do this would be defining a custom Contact-class. Classes are a concept closely related to objects. Classes can be thought of as “templates” to create different objects that behave similarly. That way, we can create variables of type contact, instead of using a dictionary. The upside is that we can choose exactly how our contact datatype should behave.

class Contact:

def __init__(self, name, email=None, cellphone=None):

self.name = name

self.email = email

self.cellphone = cellphone

With this class defined, we can now create new contact objects as follows

contact = Contact("Lisa", email="lisa@python.org", cellphone="767828292")

print(contact.email)

lisa@python.org

Our contact object is no longer a dictionary, but a Contact-object, a new data type we defined ourselves. We can check this by writing out the type:

print(type(contact))

<class '__main__.Contact'>

So far, we have only added the same information as the dictionary, but we could now go ahead and change how this object behaves. We could, for example, add a method that starts a new call, contact.initiate_call(), or a button to start an email to the person, and so on.

Class vs. Instance#

When we define a class, we define a new data type. To use it, we must define a new object of that type. We call this an instance of the class. In our contact-list example, the Contact class is the general class we defined. Then we can implement specific class instances, one for “Lisa”, one for “Frank”, and so on. The class is thus the abstract concept of a contact, and objects are the specific instances of that type.

A different example: A Nissan leaf is a given type of car and can be represented as a class. A specific car with the license plate “EM93277” (courtesy of random.org) is an instance of the Nissan leaf class. A specific car is an object of the type Nissan leaf. In this sense, the class is like the blueprint, specifying how objects of that type should be built and behave.

Naming Conventions#

According to the PEP8 style guide, class names should use the CapWords convention (aka PascalCase). This means every word in the class name should be capitalized, and the words should not be separated by underscores.

Some examples: Person, Polynomial, Vector3D, BankAccount, FileReader.

Specific instances of a class, however, should always be lowercase. So when we define a variable of a given class, we would write

u = Vector3D()

poly = Polynomial()

acc9302100 = BankAccount()

This rule is crucial to follow, as it makes it much easier to differentiate the classes themselves (the general datatype) from instances of that class (the specific objects).

Example: A deck of cards#

Time for another example. Let us say we are implementing some card games. Now, we can easily represent a deck of cards using lists of strings in Python. However, for most card games, we typically use the same operations: get a new deck, shuffle the deck, draw cards, and so on. It would be helpful to implement the code to do this once and then simply use that functionality each time we implement a new card game.

We do this by implementing a Deck class. After implementing our class, we can then define an instance of this class (deck = Deck()). Our actual game code will be much simpler because we can now call deck.shuffle() or deck.draw(5) and so on. This adds a layer of abstraction to our code and hides the ugly implementation details “behind the scenes”. This is called encapsulation, and is one of the motivations for using OOP. We can say we hide the implementation but expose an easy-to-use and easy-to-understand interface that is used to manipulate the object.

import random

class Deck:

def __init__(self):

"""Create a standard 52-card deck."""

self.cards = []

for s in ("D", "H", "C", "S"):

for v in range(1, 14):

self.cards.append((s, v))

def shuffle(self):

random.shuffle(self.cards)

def draw(self, n=1):

return [self.cards.pop() for _ in range(n)]

def shuffle_into_deck(self, cards):

self.cards.extend(cards)

self.shuffle()

Here we implement a class that has four methods. The first method is the constructor (called __init__, this is explained later). The constructor is run every time we create a new class instance. In this case, we initialize a deck of cards by adding all the cards in the deck using a double-loop. We also add a shuffle method that shuffles the deck, a draw method that draws \(n\) cards from the deck, and a shuffle_into_deck for when we want to shuffle cards back into the deck. These are just simple examples of functionality that makes sense for a deck of cards, and we could add plenty more.

Once we have taken the time to build the Deck class, we can easily create decks of cards and use them without having to think about the underlying details of the implementation. Implementing a class, therefore, represents adding a new layer of abstraction to our code. For example, we can now create a random 5-card poker hand as follows:

deck = Deck()

deck.shuffle()

hand = deck.draw(5)

print(hand)

[('C', 10), ('S', 7), ('S', 6), ('S', 12), ('S', 9)]

The use of self#

In all the examples in the chapter so far, we have used the self-syntax without explaining it. It is a common point of confusion for those learning Python, and even those who learn how to define the classes and method using self might not understand why it works as it does.

When we call a method on a given instance of a class, for example

deck.shuffle()

This is interpreted behind the scenes by Python as

Deck.shuffle(deck)

Thus, the method Deck.shuffle() acts like a stand-alone function, even though it is written inside the class. The object is passed in the function and manipulated. When we define the function, we call the first input-argument self because this is the object itself (in this case, self = deck). Note that one can technically call this argument something other than self, as it is just a function argument like any other. However, it is considered good code style to always use self. Using something other than self is often confusing. (Most languages use either “self” or “this”).

For most class methods we define, self is passed as the first argument, where we use self inside the method to manipulate the data within the object. Let us look back at the Deck.shuffle() method:

class Deck:

...

def shuffle(self):

random.shuffle(self.cards)

When we intend to use this on a specific deck, we write deck.shuffle(), without arguments. We still define the function with a self argument, and the method shuffles the internal list attribute of the deck, i.e., self.cards.

Interfaces#

In our deck of cards example, we have specific methods the user can use to interact with the deck of cards, and we can call this the interface (På norsk: grensesnitt) of the class. The interface is what is “visible” or usable from outside the class. For a large and complex class, all anyone needs to interact with it is a good understanding of its interface. In this sense, the interface itself is an abstraction tool. Take a car, for example. The interface used for driving that car is the steering wheel, the pedals and the gear stick. However, under the hood, there is an engine and complicated machinery.

Encapsulation is the act of hiding dirty implementation or technical details under the hood. Encapsulation helps keep code nice, tidy and user-friendly. Also, the details under the hood can change without issue as long as the external interface remains the same. A mechanic can replace the engine in a car, but the driver will still be able to drive it as before because the interface is the same.

In some languages, like Java and C++, we can explicitly define interfaces that define what a class must contain. These are often described as “contracts” as they state what a given class that follows that interface must contain.

Polymorphism#

The fact that we can use callable objects as if they were functions is handy, and it is an example of polymorphism. Polymorphism is another of the pillars of OOP, but the concept is challenging to define or understand. The term itself comes from greek and means “many forms”. It is a means of generalizing code, in that we can write different code that behaves the same under given circumstances, and thus we can use those objects as long as they have a given property we need. We can create objects that act and feel like functions and use them for any purpose where we need a Python function.

This is an example of Python’s duck typing. This term comes from the saying:

If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

What we mean by this is that what type a given object is, is not that important. What is important is how it behaves. We should not check whether a given input is a Python function. Instead, we should check whether it is callable. This can be done with the built-in function

callable(f)

This function returns True if the object f is callable and False if it is not. It does not care whether f is a Python function, a custom class or a given class method, analogous to the above-mentioned saying.

Example: The derivative class#

In mathematics, Newton’s method is a numerical method for finding the roots of a mathematical function (a root is a point where the function is equal to zero). Usually, Newton’s method needs the function itself \(f(x)\) and its derivative \(\frac{\rm d}{{\rm d}x} f(x)\) (which also is a function), and an initial guess \(x_0\).

Let us now assume we are given a function newton(f, x0, dfdx) that implements Newton’s method. The SciPy library, for example, has the function scipy.optimize.newton(func, x0, dfdx). We want to use this function to find the roots of a function \(f(x)\). However, suppose we lack a function for the derivative \(\frac{\rm d}{{\rm d}x} f(x)\), and we cannot find the expression for the derivative analytically. What do we do?

One solution would be to implement the derivative function numerically. We can approximate the derivative function at any point using the central finite difference

Typically we compute this for a given array of values. However, for newton to work, we can not send in an array of values. We must send in a callable function. To create such a callable function, we can create a Derivative class that automatically creates a callable object for \(\frac{\rm d}{{\rm d}x} f(x)\).

class Derivative:

def __init__(self, f, dx=1e-6):

if not callable(f):

raise ValueError("Input must be callable.")

self.f = f

self.dx = dx

def __call__(self, x):

dx = self.dx

return (self.f(x + dx) - self.f(x - dx)) / (2 * dx)

Here we create the class from a given function f, which we double-check is callable. We store the function as an attribute so we can use it later. We also store the step size \(\Delta x\), which defaults to \(10^{-6}\) if we do not supply it.

We can now implement the derivative of any callable function as its own callable object as follows

import numpy as np

f = np.sin

dfdx = Derivative(f)

Here f represents the function \(f(x) = \sin(x)\), while dfdx will be its derivative. Let us check if it works. As we know the derivative of \(\sin(x)\) is \(\cos(x)\) we can test our implementation as follows

x = 0.8281

print(dfdx(x))

print(np.cos(x))

0.6762766107115681

0.6762766106824172

With the Derivative class implemented, we can now easily use the newton method on any function. We use the Derivative-class to define the derivative function automatically and then call Newton, as follows

from scipy.optimize import newton

def f(x):

return x**2 + 4 * x + 4

dfdx = Derivative(f)

x0 = 0

print(newton(f, x0, dfdx))

-1.9999999845691476

Here we used Newton’s method as an example. scipy.optimize.newton does not require us to supply the derivative function, as it automatically implements it in the same way as we have done here.

newton(f, x0)

-1.9999999803073025

Implementing the Derivative class ourselves makes it more apparent how SciPy can use Newton’s method without having the derivative function - it is also an excellent example of how OOP can be used in scientific computing.

Properties#

Another important topic is properties, which are convenient when implementing and using custom classes. Consider the following class Sphere, which is a class that takes a radius as the argument in the constructor and stores the area and volume as attributes on the instance.

pi = 3.141592653589793

class Sphere:

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

self.area = 4 * pi * radius**2

self.volume = 4 * pi * radius**3 / 3

def __str__(self):

return f"Sphere({self.radius})"

We have also implemented a simple __str__ method so that the sphere is printed nicely when we try to print it; see Printing out instances of custom classes.

Here we set the sphere’s radius once we create the object, and the area and volume are automatically computed. This works quite well, but it has a few issues as well. For one thing, nothing prevents us from changing one of these fields directly. If we do this, the other fields do not change automatically

ball = Sphere(5)

print(f"{ball} has a volume of {ball.volume:.0f}")

ball.radius += 5

print(f"{ball} has a volume of {ball.volume:.0f}")

Sphere(5) has a volume of 524

Sphere(10) has a volume of 524

Here we created a Sphere-object, which we call ball. We can update the radius of the ball by changing the ball.radius attribute directly. However, when we do this, the volume does not change. This is because the volume is only computed in the constructor (the __init__ method), which is called only when the object is first created.

How big a problem this is, depends on how the code is used. Let us say we want to make the code more intuitive, user-friendly and foolproof. Our goal is to make it possible to change the radius attribute directly and have the area and volume auto-update.

A simple solution is to make the area and volume attribute methods instead of data fields:

class Sphere:

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def area(self):

return 4 * pi * self.radius**2

def volume(self):

return 4 * pi * self.radius**3 / 3

def __str__(self):

return f"Sphere({self.radius})"

We can now update the radius property, and when we call the area() or volume() methods, they will recompute using the new radius

ball = Sphere(5)

print(f"{ball} has a volume of {ball.volume():.0f}")

ball.radius += 5

print(f"{ball} has a volume of {ball.volume():.0f}")

Sphere(5) has a volume of 524

Sphere(10) has a volume of 4189

By making the area and volume attributes methods, they will always be recomputed as they are needed. It will also make it easier for the user to understand that they are derived quantities from Sphere.radius and not independent attributes.

However, this implementation can also be confusing. For one, radius, area and volume are different properties of a Sphere, and all are represented as numbers. So why should one be a number variable while the other methods must be called?

print(type(ball.radius))

print(type(ball.area))

print(type(ball.volume))

<class 'int'>

<class 'method'>

<class 'method'>

Let us look at a different way to set up this class using properties in Python. To do this, we use the built-in decorator @property. A decorator is something we write right before a function/method definition, and it will change the functionality of that function/method in some way. Project 0 explores an example of a decorator.

When we add the @property decorator to a method in a class, that method will behave as a data field outside the class.

class Sphere:

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

@property

def area(self):

return 4 * pi * self.radius**2

@property

def volume(self):

return 4 * pi * self.radius**3 / 3

def __str__(self):

return f"Sphere({self.radius})"

football = Sphere(11)

print(football.area)

print(type(football.area))

1520.53084433746

<class 'float'>

Here, Sphere.area and Sphere.volume are defined in the same manner as before, but we have added the code @property right before the method definitions. By adding this decorator, we can now treat football.area as a data field, i.e., a number variable. This means we can print it out without calling it as a method. I.e., print(football.area) instead of print(football.area()). If we print out the type, it confirms that it is indeed a float.

Using the property decorator allows us to implement a method that compiles or computes the data behind the scenes. It also allows the user to treat that property as a data field on the outside. We can now change the radius, and the area and volume properties will also change. The user does not have to think about this themselves.

ball = Sphere(5)

print(f"{ball} has a volume of {ball.volume:.0f}")

ball.radius += 5

print(f"{ball} has a volume of {ball.volume:.0f}")

Sphere(5) has a volume of 524

Sphere(10) has a volume of 4189

Let us now look at what happens if we change the area and volume properties directly instead of changing the radius.

football.area = 1200

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[19], line 1

----> 1 football.area = 1200

AttributeError: can't set attribute 'area'

Thus, by defining an attribute using @property, we have effectively made the attribute “read-only”.

Setters and Getters#

In Python, we can access class attributes directly using the dot notation, e.g., ball.radius, and we can also change these directly if we so desire. This is not considered bad practice if the class is defined to do this. In many other languages, however, one cannot access attributes directly, or it is considered bad practice to access them directly. It is common to define “setter” and “getter” methods in such languages. Here we would define a Sphere.get_radius method, which would return the value of the radius, and we would define a Sphere.set_radius to redefine it.

In Python, such setters and getters are usually not implemented explicitly, but we can use the same logic. In our previous example, we defined

@property

def area(self):

return 4 * pi * self.radius**2

This method is effectively a getter for the area. It is not called get_area, but that is what the function does.

Similarly, we can define a setter method for the area property using the decorator @area.setter. Let us show an example

from math import pi, sqrt

class Sphere:

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

@property

def area(self):

return 4 * pi * self.radius**2

@area.setter

def area(self, area):

if area < 0:

raise ValueError("Area cannot be negative")

self.radius = sqrt(area / (4 * pi))

def __str__(self):

return f"Sphere({self.radius})"

Here we first define the Sphere.area property using @property, allowing us to access Sphere.area as if it were a number variable. After this, we also define a setter, allowing us to redefine (or “set”) the area. To do this, we have to use the area formula in reverse to find the equivalent radius and redefine self.radius.

With the @area.setter method defined, we can now both access Sphere.area and redefine it if we want. For example:

ball = Sphere(10)

print(f"{ball} has an area of {ball.area:.0f}")

ball.radius = 5

print(f"{ball} has an area of {ball.area:.0f}")

ball.area = 1000

print(f"{ball} has an area of {ball.area:.0f}")

Sphere(10) has an area of 1257

Sphere(5) has an area of 314

Sphere(8.920620580763856) has an area of 1000

So we now have a Sphere class that allows us to either set the radius and have the area automatically update, or we can set the surface area, and the radius automatically updates. Hopefully, it is apparent why this could be useful. Another detail about this is that we can build in some controls on the input of the setter function. Note that we, in the @area.setter method, have a check to see if the area is negative. If Sphere.area were a simple float attribute, we would have no way of restricting what value it was set to in this manner.

ball.area = -1

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[23], line 1

----> 1 ball.area = -1

Cell In[21], line 15, in Sphere.area(self, area)

12 @area.setter

13 def area(self, area):

14 if area < 0:

---> 15 raise ValueError("Area cannot be negative")

16 self.radius = sqrt(area / (4 * pi))

ValueError: Area cannot be negative

Using the setter, attempting to set a negative area now throws the exception ValueError.

As a small exercise, we invite the reader to define the @volume.setter method.

Avoiding repeated computations#

Our sphere class now works quite well and is user-friendly. We can now set the radius, surface area and volume directly as floats, and the others change automatically. However, this implementation might not be that efficient, as every time the user accesses .area or .volume, the actual values are computed from the radius behind the scenes.

Recomputing the area or volume is not a big deal for such a simple application. However, it would be inefficient to perform such computations repeatedly if they were more complicated and took more time.

We would get around this by storing the computed values as internal data in the class that the user should not interact with from outside the class. Such attributes are typically called private attributes. In Python, there is no way to implement actual private variables, but one can designate that variables should be considered private by giving them names with a leading underscore.

Let us show by an example (again, we skip the volume property)

class Sphere:

def __init__(self, radius):

self._radius = radius

self._area = 4 * pi * radius**2

@property

def radius(self):

return self._radius

@radius.setter

def radius(self, r):

if r < 0:

raise ValueError("Radius cannot be negative")

self._radius = r

self._area = 4 * pi * self.radius**2

@property

def area(self):

return self._area

@area.setter

def area(self, area):

if area < 0:

raise ValueError("Area cannot be negative")

self._radius = sqrt(area / (4 * pi))

self._area = area

We now store the area of the sphere as a private attribute called sphere._area. The underscore means this variable should never be accessed from outside the class. In addition, we added the property sphere.area, which can be used from outside.

The code will now behave the same as before from outside the class. By using sphere._area we avoid unnecessarily recomputing the area many times.

Note that we have also made the radius into a private variable sphere._radius and external property sphere.radius. We had to do this to ensure that the sphere._area attribute is recomputed if the radius is set (using @radius.setter).

The code is now considerably more complex than what we started with. In many simple use cases, one would not go through the hassle of using private internal attributes like this and creating properties and setters for these. For the sphere, recomputing the area a few times consumes close to no resources and can easily be done to get a simpler code. We simply use this as an example of how to handle cases that would be more complex.

Private and Public variables#

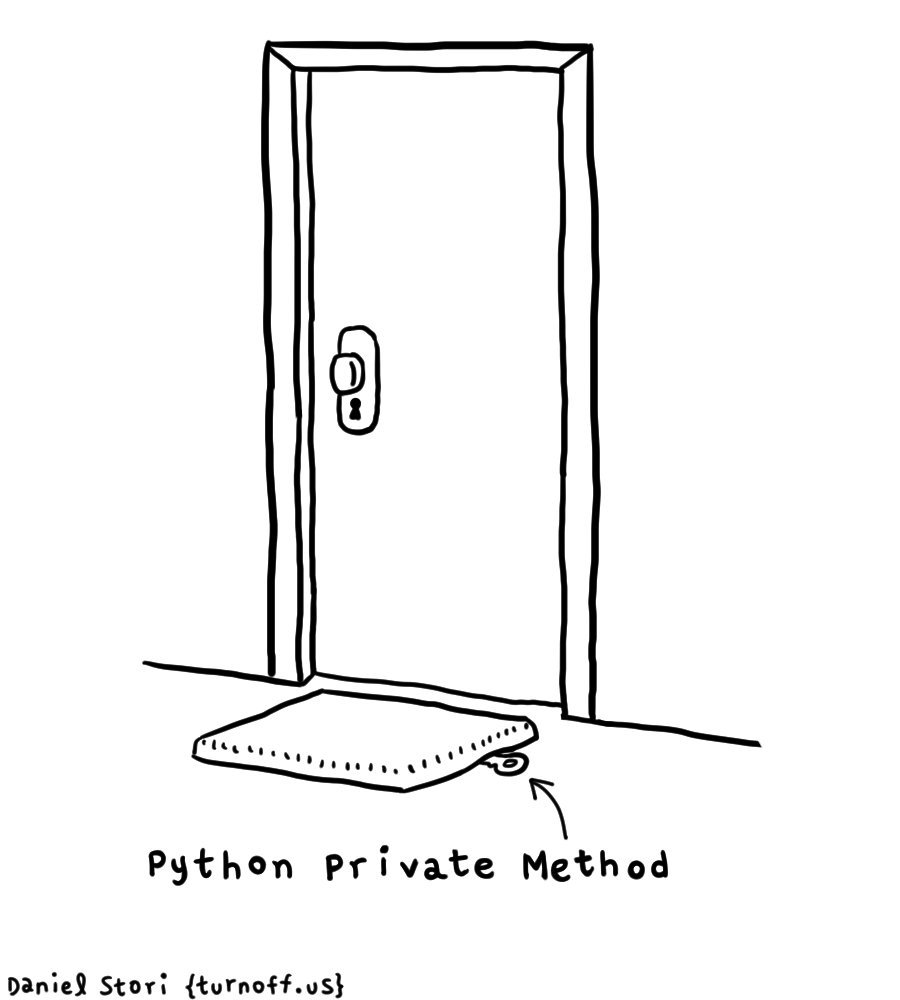

In our final example, the user has the properties football.radius and football.area they can interact with, while the class stores the internal data in the fields _radius and _area. We call the first two public properties or variables. Here, public means that they are accessible from outside the class. The latter two variables are private, meaning they should only be accessed from inside the class and are not meant to be used outside.

Note that we give the private variables leading underscores in their name, which indicates they are private. There is no way to enforce private variables in Python, and the leading underscore is just a convention. Thus the user can change these directly: football._radius = 9. However, this would be breaking the convention that one should not change a private variable, and if this breaks the object, it is the user’s fault. Other languages, such as Java and C++, do enforce private and public variables (an error is thrown if one attempts to access a private variable outside the class).

Fig. 8 Private attributes in python are not really private.#

Dataclasses#

When writing a class, we have to write a lot of boilerplate code. Dataclasses is a technique to reduce boilerplate code. Consider the Contact class that was introduced at the beginning of this section.

class Contact:

def __init__(self, name, email="", cellphone=""):

self.name = name

self.email = email

self.cellphone = cellphone

def __str__(self):

return (

f"Contact(name={self.name}, email={self.email}, cellphone={self.cellphone})"

)

Here we have changed the default values for email and cellphone from None to an empty string (""). We will see later in this section how to deal with None. We have also added a special method __str__ which ensures that an instance is printed adequately; see Printing out instances of custom classes. We can create an instance and print it

p = Contact(name="Henrik", email="henriknf@simula.no")

print(p)

Contact(name=Henrik, email=henriknf@simula.no, cellphone=)

What we noticed here is that there is a lot of repetition in the code. First, we must specify the arguments in the __init__ function, and then we are required to set the attributes on the instance. Finally, we must access the same attributes to make an aesthetic print function. This is just a class that holds some data, a widespread use case for a class. Because this is a common pattern, Python introduced a new concept in Python3.7 known as dataclasses that will simplify the process of creating these types of classes.

Before introducing dataclasses, we will also add type annotations to the arguments (see Type annotations for more information) and methods since this is required when working with dataclasses. We can add types to the Contact class as follows

class Contact:

def __init__(self, name: str, email: str = "", cellphone: str = "") -> None:

self.name = name

self.email = email

self.cellphone = cellphone

def __str__(self):

return (

f"Contact(name={self.name}, email={self.email}, cellphone={self.cellphone})"

)

We are now ready to transform this class into a dataclass. This is done by importing dataclass from the dataclasses modules and adding the dataclass decorator to the class.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Contact:

name: str

email: str = ""

cellphone: str = ""

We can now try to redo the example above and create an instance and print it

p = Contact(name="Henrik", email="henriknf@simula.no")

print(p)

Contact(name='Henrik', email='henriknf@simula.no', cellphone='')

Interesting, right? The two examples above are equivalent, but we can write less code when using dataclasses. We also see that adding type hints improves readability, documentation, and IDE integration. Win-win!

Let us go back to the original Contact class where email and cellphone were set to None.

email and cellphone should be strings, but if no value is provided, they should have a default value None. The type of such a variable is Optional[str], where Optional is imported from the typing module (again, see Type annotations for more information).

import typing

class Contact:

def __init__(

self,

name,

email: typing.Optional[str] = None,

cellphone: typing.Optional[str] = None,

) -> None:

self.name = name

self.email = email

self.cellphone = cellphone

def __str__(self) -> str:

return (

f"Contact(name={self.name}, email={self.email}, cellphone={self.cellphone})"

)

p = Contact(name="Henrik", email="henriknf@simula.no")

print(p)

Contact(name=Henrik, email=henriknf@simula.no, cellphone=None)

Translating this to a dataclass results in

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Contact:

name: str

email: typing.Optional[str] = None

cellphone: typing.Optional[str] = None

p = Contact(name="Henrik", email="henriknf@simula.no")

print(p)

Contact(name='Henrik', email='henriknf@simula.no', cellphone=None)

It should be noted that dataclasses are just regular classes, but with some extra syntactic sugar to make it simpler and to avoid writing too much boilerplate code. Methods can be added to this class, similarly to a regular Python class.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Contact:

name: str

email: typing.Optional[str] = None

cellphone: typing.Optional[str] = None

def has_email(self) -> bool:

return self.email is not None

def has_cellphone(self) -> bool:

return self.cellphone is not None

def make_phone_call(self) -> None:

if not self.has_cellphone():

print(f"Cannot call {self.name}. No phone number available")

return

print(f"Calling {self.name} at {self.cellphone}...")

p1 = Contact(name="Henrik", email="henriknf@simula.no")

p1.make_phone_call()

p2 = Contact(name="Elon Musk", cellphone="12345678")

p2.make_phone_call()

Cannot call Henrik. No phone number available

Calling Elon Musk at 12345678...

The arrows in the function definitions mean what return type the function should return. For example, def has_email(self) -> bool: means that has_email returns a boolean value.

To learn more about dataclasses, check out the Dataclasses guide on realpython.com.

NamedTuple#

In the dataclass example above we could also obtain the same result using a NamedTuple. In that case, the code would look as follows

class ContactNamedTuple(typing.NamedTuple):

name: str

email: typing.Optional[str] = None

cellphone: typing.Optional[str] = None

def has_email(self) -> bool:

return self.email is not None

def has_cellphone(self) -> bool:

return self.cellphone is not None

def make_phone_call(self) -> None:

if not self.has_cellphone():

print(f"Cannot call {self.name}. No phone number available")

return

print(f"Calling {self.name} at {self.cellphone}...")

p1_named_tuple = ContactNamedTuple(name="Henrik", email="henriknf@simula.no")

p1_named_tuple.make_phone_call()

p2_named_tuple = ContactNamedTuple(name="Elon Musk", cellphone="12345678")

p2_named_tuple.make_phone_call()

Cannot call Henrik. No phone number available

Calling Elon Musk at 12345678...

Notice that here we inherit from typing.NamedTuple (more about inheritance later in the material).

So what is the difference? The difference is that dataclasses are regular (dynamic) classes. This means that, for example, assigning new attributes to the instance is allowed, i.e.,

p1.new_attribute = 42

When creating a named tuple, we are not creating a regular class but a “fancy” tuple. As we have seen, tuples are immutable data structures, which means that changing them after creation results in an error.

p1_named_tuple.new_attribute = 42

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[35], line 1

----> 1 p1_named_tuple.new_attribute = 42

AttributeError: 'ContactNamedTuple' object has no attribute 'new_attribute'

NamedTuple vs Dataclass vs Regular Class?#

It is recommended to start with a named tuple, and if it does not work (for example, if we need to set attributes dynamically), then dataclasses should be used. Again, if that does not work (for example, if we need to do something more advanced in the initializer), one might be better off just using a regular class. Choosing a regular class also benefits from the fact that nothing needs to be imported, nor do we have to use inheritance (for NamedTuple) or a class decorator (for dataclasses).