An introduction to C++#

In C++, we start to turn to a new programming language, C++, which, in combination with Python, will be used for the rest of the material. We discuss how to read and write short C++ programs and how to compile and run them. The goal is to familiarize the reader with C-style code and also to highlight the major differences between Python and C++. Note, however, that the world of C++ is extensive, and to get proficient in C++, one has to dedicate a lot of time and effort to it. The goal is, therefore, to give an overview of the language that can be useful in the future.

C++ has the fame of being an extremely hard language to learn and use. While that might be an exaggeration, it is definitely a more technical language than Python. Nonetheless, the goal of this material is to write some interesting programs rather than to absolutely master all the concepts.

A Python to C++ transition guide#

The book Object-Oriented Programming in Python, written by Michael H. Goldwasser and David Letscher, has a supplemental document called A Transition Guide from Python 2.x to C++* by Goldwasser and Letscher. The supplement is approximately 90 pages and covers most of what we will be covering in C++. Notice that this supplement is written for Python 2, but the differences are minor for the scope of our applications.

Another great resource is C++ for Python programmers guide, which contains interactive code samples and quizzes.

The definitive C++ book guide and list#

If a dedicated C++ book is desired, there exist many out there. The following list, Definitive C++ Book Guide and List, contains several recommendations according to the reader’s previous programming experiences.

Why C++?#

So why are we learning C++ as our second language?

C++, like many other programming languages, is based on C, which was created in 1972 but is still widely used today. C is a low-level language that compiles into highly efficient machine code, and it is incredibly fast. While C is important historically, it is still one of the most used languages today, with several commonly used software, such as UNIX and the main implementation of Python, being written largely in C. One particular example the reader might be familiar with is Python’s NumPy library. NumPy allows high-performance manipulation of array objects in Python, and the reason behind its speed is that a substantial part of it is written in C.

C++ is a direct extension of the C programming language, with the motivation of adding classes. The syntax and semantics of the two languages are, therefore, nearly identical. The major difference is that C++ has larger standard libraries and more support for higher-level constructs, such as object-oriented programming. Nonetheless, C++ still retains most of the low-level features of C and, if implemented correctly, will be highly efficient and fast.

Several other popular languages are also, at least partially, based on C, such as C# and Objective-C. Other languages, like Java, borrow most of their syntax from C. While Java and C are very different in the way they fundamentally work and run, the code itself looks fairly similar. In short, many languages today have a strong “C-flavor” to them, and dedicated programmers are often expected to know a C-style language.

In summary, the reason for learning C++ is multifold: Knowing a C-style language is extremely useful for any programmer, and it makes it easier to learn any other programming language. Also, we want a highly efficient language capable of making large computations fast. This requirement justifies the choice of C or C++ over Java. Lastly, as we are learning object-oriented programming, C++ is the natural choice over C.

How to write, compile and run C++ programs#

As a first introduction to the language, let us write a Hello, World program by opening a text editor of choice and creating a new file called hello_world.cpp.

Here, note that .cpp is a file extension for C++ source code, i.e., the file we write the code itself. This is only one possible file extension, and other common ones are .cc, .cxx, or .c++. The convention hereon will be to use .cpp.

Some people advocate using IDEs for C++ (such as Qt Creator). For larger projects, this can be very helpful as IDEs help with linking many different files and other practicalities. For the current discussion, however, we limit ourselves mainly to single-file C++ programs, and getting a dedicated C++ IDE is unnecessary.

First C++ program#

Before starting to write, compile and run any C++ code, it is important to read through the C++ installation guide.

In the recently created .cpp file, we enter our Hello world code, which will look like the following

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello world" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Hello world")

We also included the Python Hello world code for comparison. The if __name__ == "__main__" block is included to make the two examples look more similar, but it is strictly not necessary.

Before covering how to compile and run this code, let us read through and analyze what is happening in the C++ version.

The program starts with an #include statement, equivalent to importing files or packages in Python. This statement means we include a so-called header file (more on headers later). Here the standard header iostream (input-output stream) is included, allowing the output of the desired message.

Next, a function named main is defined. In C++, we have to define a main function, and executing the program is the same as calling this function. It has to be specifically named main, or an error is generated. This function can be interpreted as the program’s starting point and will be executed when running the program directly. In fact, this is not too different from what Python does with the if __name__ == "__main__" block. The main block in Python is, however, far less restrictive.

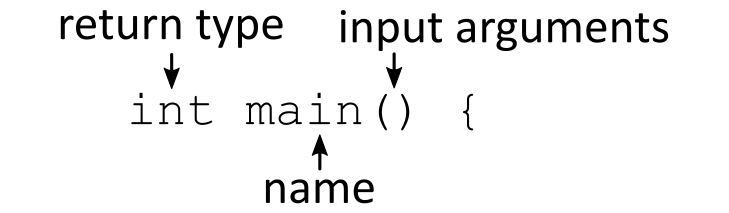

We write int main() because the function returns an integer (see Exit codes), is named main, and takes no input. Note that the contents of the function go between two curly braces ({ }).

Fig. 25 Declaring the main function of a C++ program.#

Inside the main function, we do two things

Write out the message

Return the integer 0

When writing out the message, we use the object std::cout. Despite not being the only way to print in C++, it is the recommended one. Here, std::cout is an output stream, and anything inserted into this stream will be written out. We insert characters using double-angle brackets (<<) and write out messages as a text string, using " as delimiters. In Python, we use " and ' interchangeably, but in C++, " denotes string literals, while ' denotes single character literals. Additionally, the output line ends with a semicolon(;), as every statement in C++.

Writing std::cout << a << b simply outputs a and b in order. Notice that after inserting the message, we also include std::endl. Here endl stands for end line, and is essentially a newline character. An alternative to inserting std::endl would have been to include a newline character in the string: "Hello, world!\n". There is a subtle difference between using endl and \n, which is further discussed in StackOverflow.

Including std:: means we are accessing something contained in the std namespace and is necessary as we are using variables that come from this iostream standard header. If importing from other packages, different namespaces are needed, such as arma:: (for the Armadillo libraries) or boost:: (for the Boost libraries).

In programs developed here, there will not be many packages used, and we will mostly use standard headers, meaning the code contains several std:: inclusions. Writing that many identical terms can become tiresome and, to avoid this, using namespace std; can be declared at the top of the program. When the program then calls a function, this declaration instructs the compiler to look for the given function in the std namespace. Consequently, std::cout can be replaced by just cout whenever a message is output. For the hello_world.cpp script, the resulting degree of simplification is small, but in larger codes, having a single declaration instead of dozens of std:: can be preferable.

Finally, we return 0 from the main function by writing return 0; (the same as in Python, except for the fact the statement needs to end with a semicolon). After returning, the function declaration is concluded, so we include a closing curly brace (}). When the program finishes, we should return something to the system so that it knows the program is done running. As mentioned, the main function is the function called by the system when the program is executed. It is customary to return an integer, in which case 0 is used to indicate the program terminated successfully. If the program aborts or crashes, any other integer is returned. Depending on what caused the erroneous termination, we can return a different number, which would be an error code, telling the system something about what went wrong. Error codes will not be used extensively in this material. Simply put, we always return 0 at the end of our main function, and if something goes wrong, we will instead throw an exception.

Compiling and Running C++ programs#

We have now written and analyzed a C++ code, but how do we actually run it? Here, the procedure differs from Python because C++ code needs to be compiled before it can be run.

Interpreted vs. Compiled Languages#

One of the major differences between Python and C++ is that Python is an interpreted language, while C++ is a compiled language. When writing a Python program, the source code and the programs are one and the same. To run the program, we invoke the Python interpreter, which reads our code and executes it as it is read.

For C++ programs, however, we write our code to a file, but this file cannot be executed directly. Instead, the source code must be converted into an executable program, and this step is known as compiling the code. This compilation is done by invoking a C++ compiler that reads the code. However, unlike the Python interpreter, the compiler does not execute code. Instead, it translates it into low-level executable machine code, making sure to specialize the code to the system we are compiling on. As a result, this process generates an executable, a file that can be executed to run the program. This program is now executed directly by our machine, and we do not need to invoke a separate “C++ interpreter” as the source code has already been translated to code the machine can understand. This difference between C++ and Python is one of the main factors for their discrepancy in speed: in general, compiled languages are faster than interpreted ones. While interpreting each line at runtime comes with some overhead, compiled code can be pre-processed and optimized.

Note

Python does also perform a compilation step where the source code (the text in the .py file) is compiled to something called bytecode which are files with the suffix .pyc that appear in a folder called __pycache__. In that regard, Python is also a compiled language, but we typically think of compiled languages as languages that compile the code into machine instructions, such as C++. More about this topic can be investigated in this thread.

Most editors and IDEs have some functionality to compile (also called building) C++ source code into executables, and learning these could be good for workflow. However, it is still important to learn how to do it “manually” in the command line as well.

Different compilers can be used depending on the choice of the operational system. When using Linux, the GNU compiler GCC, one of the main C++ compilers, is probably already the default. On Windows, it is equally possible to use GNU (through, for example, Cygwin), but perhaps more common is to use Visual C++. Many other C++ compilers exist. On macOS, the default compiler is called Clang, which is also very popular.

Installing a C++ compiler is meant as a guide to help with the installation process of a C++ compiler.

How to compile a program#

We will now compile the previous C++ code by invoking the compiler in the terminal. The following examples make use of the GCC compiler and should change slightly with a different compiler.

If the reader does not have a compiler installed yet, the material in installation instructions is strongly recommended before moving on.

If using GCC or Clang, the C++ compiler is invoked in the terminal by writing c++, followed by which source code should be compiled

c++ hello_world.cpp

Executing a program#

When we run c++ to compile code, the compiler analyzes the code. In case a specific set of errors, called compilation errors, are not found, it creates an executable. However, if we have not specified a name for the resulting executable, it defaults to the filename a.out.

To run the a.out executable, we can invoke it directly

./a.out

If everything is done correctly, running this program gives us the expected “Hello world” output.

Note that errors can be generated both in the compilation of the program and its execution. The compiler might protest and abort when compiling the source code, in which case we get no executable. Analogously, the compiler might execute without any issue, but when running the source code result in errors. The compiler tries to detect errors before execution and will catch syntax and some semantic errors. However, other types of errors not found by the compiler will be present in the final executable program.

Naming executables#

The name a.out is generic and not very descriptive. To improve this, we should compile programs into an executable with a specific name. This is done by adding an output-flag: -o name as follows

c++ hello_world.cpp -o hello

The above creates an executable called hello, which we would run directly in the terminal as

./hello

Note that we do not give this executable any file extension. This is very common for executables on UNIX machines. On Windows, the executables are often given the ending of .exe, short for executable.

Note also that the output name can be put before the source code

c++ -o hello hello_world.cpp

The order is just a personal preference.

Other compiler flags#

Other flags can be added to the compiler to give it special instructs or extra information. A common one to include is -Wall (for “Warning all”) that tells the compiler to give warnings if there are points in the code that could be potentially problematic while not entirely wrong. This flag can be passed as

c++ hello_world.cpp -o hello -Wall

Note that warnings in this context are not the same as errors since an error causes compilation to terminate, while a warning still gives an executable. In this case, the compiler is alerting the possibility of inefficient or error-prone parts of code. Ironically, -Wall does not give all possible warnings, and more can be detected by adding -Wextra or -W flags. There are a variety of warning flag options for specific purposes.

Static vs. Dynamic Typing#

One of the major differences between C++ and Python is that C++ is statically typed, while Python is dynamically typed.

This means we have to specifically declare variable types when defining them in C++. Moreover, a given variable cannot change its type. In Python, however, we declare variables and let the interpreter decide implicitly what types the variable can assume while also allowing them to change types freely.

For example

string name = "Bob";

int birth_year = 1990;

double height = 1.73;

name = "Bob"

birth_year = 1990

height = 1.73

Note that the differences are that, in C++, we need to be explicit in our typing and include semicolons at the end of a statement.

The common primitive data types in C++ are

C++ Type |

Description |

Size in memory |

|---|---|---|

|

Boolean |

1 byte |

|

16-bit integer |

2 bytes |

|

32-bit integer |

4 bytes |

|

64-bit integer |

8 bytes |

|

32-bit floating-point |

4 bytes |

|

64-bit floating-point |

8 bytes |

|

single character |

1 byte |

|

character sequence |

1 byte |

These types are different from the standard ones in Python. In C++, for example, the type float has 32-bit precision, while a double has twice that (64-bit). As a consequence, a double value takes up twice as much memory as a float value.

For scientific applications, we want the extra precisions of doubles, usually using them instead of floats. Note that the float type in Python is actually a double, as it has 64-bit precision.

Similarly, the integer type in C++ has a fixed precision of 32 bits, meaning it has a built-in lower and higher limit to what number it can contain. This is again different from the Python int type, which has no size limit and is able to store indeterminately large values. Python int size is solely limited by the system’s available memory.

Note also that the string type in C++ has to be imported from the standard library header by the same name:

#include <string>

Since a single character has a size of 1 byte = 8 bits, it can hold \(2^8 = 256\) different characters. Therefore, a 32-bit integer can hold \(2^32 = 4294967296\) different values, and since we include the negative values as well, the typical range of a 32-bit integer is between -2147483648 and +2147483647 (with zero included). This means that to work with larger integers than this, using long, which has a range of \([-2^{63}, 2^{63} - 1]\), is necessary.

Functions and Types#

It is not just when defining variables that we need to be explicit in our typing but also when defining functions. For each defined function, we have to explicitly state what types the function receives as input and what types are output.

In a Celsius to Fahrenheit conversion function, it could be done as follows

double F2C(double F)

{

return 5 * (F - 32) / 9;

}

Here, double F2C(...) states that we are creating a function F2C that returns a double, while (double F) states that it takes a double as an argument. The contents of the function itself are put inside curly braces ({}). The desired output is made explicit by the return keyword.

Similarly, if we want to create a function is_prime, that takes in an integer and returns true or false,

bool is_prime(int n)

{

...

}

This statement is called the signature of the function. The combination of a good function name and typed input and output should give the reader a good understanding of what the function does.

What do we do if we want to make a function that returns nothing? Then we define it as a void, which simply means it does not return anything

void greet(string name)

{

std::cout << "Hello there " << name << "!" << std::endl;

}

A full program that defines and uses the F2C function can look as follows

#include <iostream>

double F2C(double F)

{

return 5 * (F - 32) / 9;

}

int main()

{

double temp = 110.;

std::cout << temp << " F" << std::endl;

std::cout << F2C(temp) << " C" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Here we first define the F2C function followed by the main function.

Loops and if-tests#

The most common loops in Python are the loops using range. Let us investigate how to create loops in C++ by comparing two simple examples in both languages

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

std::cout << i * i << std::endl;

}

for i in range(10):

print(i * i)

In both languages, we use the for-keyword to define a for-loop. However, the loop itself is defined differently. In C++, we first state where the loop should start (i=0), how long it should keep going (i<10), and how it should increment, the step (i++). Note that i++ means an increment, similar to i += 1. With this syntax, the for-loop is defined with the same logic as a while-loop. Note also that we have to explicitly type the counting variable i by writing int i=0 for the start of the loop.

Note

Notice that the order in which the plus sign appears matters. While both ++i and i++increment the values of i by 1, the former returns the incremented value while the latter returns the previous, not incremented value of i. This does not have any effect on for-loops, but the difference appears when assigning the statement to another variable. For example, j=i++ first assigns the value of i to j, and then increments i.

As with functions, the contents of the loop are put inside curly braces.

If-tests#

If-tests in C++ look exactly like in Python, except for some small differences in what symbols are used

if (i < 100)

{

i *= 2;

}

if i < 100:

i *= 2

The two important distinctions are the addition of parentheses around the condition and the use of curly braces to define the contents of the test (the scope). Python’s scope is defined by the colon and indentation. The indentation in C++ is not necessary, but this topic will be covered in the following discussion.

Boolean Operators in C++#

While the if-tests in C++ are very similar to Python’s, the conditions are slightly different. The Python boolean operators and/or/not, are also defined in C++, but are usually written as &&/||/!, respectively.

It is, however, important to be careful when combining conditions in C++. The Python expression if lower < x < upper, would be evaluated in C++ as (lower < x) < upper, with the first condition evaluating to 0 for false and 1 for true. The following example elucidates when the conditions can become different.

if (3 < 10 < 7)

{

...

}

Notice that this condition passes because “(3 < 10) < 7” is the same as “1 < 7”, which is true. In Python, however, this would not pass, as the parenthesis would not be applied.

Example: is_prime#

We now combine a for-loop and an if-test to create the is_prime function outlined earlier.

bool is_prime(int n)

{

if (n == 1)

{

return false;

}

for (int d = 2; d < n; d++)

{

if (n % d == 0)

{

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

Here, we first check the special case of \(n=1\). Then we see if any of the numbers in the interval \([2, n)\) cleanly divide the candidate, which we do with the modulo operator. Depending on the input, we return either true or false. Note that these are specified with all lower capitalization.

To test the function, we make a loop checking the numbers 1 through 11:

int main()

{

for (int i = 1; i <= 11; i++)

{

if (is_prime(i))

{

std::cout << i << " is prime" << std::endl;

}

else

{

std::cout << i << " is not prime" << std::endl;

}

}

}

A note on bracket style#

In Python, the whitespace character does not matter much, with the exception of newline characters and leading whitespace as indentation. In C++, however, whitespace matters even less, and this includes newline characters and indentation. As we always include semicolons at the end of statements in C++, we do not need to use newlines between different statements, and because we use curly braces to define scopes, we do not need to use indentation.

However, while newlines and indentation are not strictly necessary for the code to function, we should use them to increase structure and help readability. Since newlines and indentations do not impact the code behavior, they can be used in different ways, giving rise to distinct style choices. In C and C++, there are several style choices of indentation, newlines, and bracketing, one of the most well-known being the Google C++ Style Guide.

One major point of contention is whether to place the opening brace of a function definition or a control structure on the same line as the control statement or on a separate line immediately below it

int main(){

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++){

...

}

}

or

int main()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

...

}

}

Both styles are widely used, and it comes down to preference. More important than style choice is, however, style consistency. For example, if one prefers the first style, called the “One True Brace Style” (OTBS/1TBS), then one should use this style in the whole code file or repository.

Pro tip: Use a formatting tool

To avoid thinking too much about the bracket-style (or coding style in general), a good tip is to use a formatting tool. For Python, we have seen black and autopep8. A similar tool exists for C++, and the most popular one is probably clang-format which comes already installed with gcc as well as clang. The file can then be formatted by using the command clang-format hello.cpp -i, or if using VSCode, it is possible format on save by adding "editor.formatOnSave": true in the settings. More about different styles can be checked in the Clang documentation.

Single-statement loops and tests#

Another important thing to note about braces in C++ is that in a control structure with a single statement, it is possible to skip the braces altogether. For example,

if (is_prime(i))

{

std::cout << i << " is prime" << std::endl;

}

else

{

std::cout << i << " is prime" << std::endl;

}

could just as well be written

if (is_prime(i))

std::cout << i << " is prime" << std::endl;

else

std::cout << i << " is prime" << std::endl;

Some prefer to write the latter because it looks less convoluted without the brackets. The OTB style states that this should not be done, however, as it can easily lead to errors.

When always using braces, even for single statements, it is always possible to simply add more statements later. However, if additional statements are added while omitting braces, the statements are understood to be outside the control structure. This means the first style is considerably safer and more extendable than the second. Consequently, the recommendation is to always use braces, as it will prevent bugs that can lead to frustration and cost time down the road.

While-loops#

While-loops in C++ are also similar to Python’s. Just like the if-tests, we put parenthesis around the condition and define the scope using curly braces

int n = 1;

while (n < 10)

{

n *= 2;

}

n = 1

while n < 10:

n *= 2

As we can see, there is close to no difference.

Vectors#

The Python list data type is not built into C++ in the same way. While there exists a data type called a list in the C++ standard library, it does not behave like Python’s when it comes to dealing with data type. A closer analogy to Python list in C++ is called a vector, available from one of the standard libraries. It can be included by using

#include <vector>

We will later return to why vectors are equivalent to Python lists when we discuss data structures.

One major difference between Python lists and vector objects in C++ is that vector objects must contain elements of the same type. So when defining a vector object, we must not only declare that the variable is of type vector, but we must also define the type of the elements. This is done as follows

std::vector<int> primes;

Here, we define a variable primes, that is of type vector, with contents of type int. The use of <int> is called templating.

Note that the primes vector will start out as an empty vector (we do not need to specify it as being empty, this is implied). If, however, we wanted to initialize it with given elements, this could be done as follows

std::vector<int> primes{2, 3, 5, 7, 11};

Note that we do not use any = for assignment here. More on this will be discussed later when we turn to OOP in C++.

Interacting with C++ vectors#

As stated, the C++ vector objects behave similarly to Python lists, and we can also access and change specific elements using square bracket indexing. C++ also starts indexing at 0, so primes[3] refers to the integer 7 in the list of primes initialized above. However, note that Python-like slicing is not applicable for indexing here.

To append elements to a vector, use the method .push_back(n), which adds elements to the end of the vector. To get the number of elements in the vector, use .size(). To see other supported methods, check the reference.

Pro tip: Install a C++ extension to the text editor

Most modern editors and IDEs come with extensions that can make it easier to see which methods are available and provide documentation for those method. A popular choice is the C/C++ tools extension, which provides both intellisense and debugging features.

In Python, we can easily loop over elements in a list

for p in primes:

...

A similar syntax is possible with vectors

for (int p : primes)

{

...

}

or, alternatively, it is possible to loop over the indices

for (int i = 0; i < primes.size(); i++)

{

// do something with primes[i]

}

Example: Finding primes#

Let us now define a function that finds the first \(n\) primes. To do this, we will use the is_prime function defined above.

First, we need to define the signature of our function. It should return a vector of integers and take in the number of primes to find, so we write

std::vector<int> find_primes(int nr)

{

...

}

Now, inside the function, we first need to define an empty vector, inside which new primes can be pushed as they are found. We can then use a while-loop to check primes.size() < nr until we have found enough primes.

The whole function becomes:

std::vector<int> find_primes(int nr)

{

std::vector<int> primes;

int n = 1;

while (primes.size() < nr)

{

if (is_prime(n))

{

primes.push_back(n);

}

n++;

}

return primes;

}

To test the function, we add the following to the main function:

int main()

{

std::vector<int> primes = find_primes(100);

for (int p : primes)

{

std::cout << p << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Compiling the program and running the executable will now write out the first 100 primes.

Strings#

We now turn to string objects. C has a primitive data type called char, which is a single character. Strings are sequences of characters, and to make strings in C, one creates arrays of characters. We will cover arrays in Arrays, References, Pointers, but for now, let us simply say they are sequences, like a tuple. Thus, C has no primitive string data type; it instead uses the char[] data type (the square brackets denote an array).

In C++, however, a string data type has been added in the standard library and is the recommended way to work with strings. Note that the data type is called string, and not str as in Python.

To use strings, we must include the header from the standard library

#include <string>

We can then use strings by writing std::string.

See the full reference on strings to see what functionality the string class adds at the reference

Type inference#

Consider the following lines of code

int x = 1;

int y = x + 1;

It is clear that both x and y are integers. However, we can also deduce that y has to be an integer because x is. Automatic detection of data types is called type inference, and since C++11 standard, we can instead write

int x = 1;

auto y = x + 1;

When using auto, C++ will figure out which type to use. Despite this being very convenient when working with complicated types, it can make the code less readable.

A better use of auto is in contexts where the type is not relevant, for example, when printing out the elements in a vector

std::vector<int> v{1, 2, 3};

for (auto x : v)

{

std::cout << x << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

Standard input and output#

We have already seen that it is possible to write output to the console using std::cout from the iostream library. The iostream library enables us to print information to the console as well as handle input from the console using the notion of streams. A stream can be thought of as a flow of data, and the angle brackets << and >> as operators acting on that stream. We use the output operator (<<) with console output (cout) and the input operator (>>) with console input (cin). Here is an example using cin

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int number;

std::cout << "Input a number: ";

std::cin >> number;

std::cout << "You entered " << number << std::endl;

return 0;

}

File streams#

Working with files is almost the same as working with the console. The following program will write a sequence of the first 10 digits to a file called output.txt

#include <fstream>

int main()

{

ofstream ofs{"output.txt"};

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

ofs << i << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Notice that we need to include the fstream library, which contains the functionality for working with files. In the line ofstream ofs{"output.txt"}; we create a file stream for writing to a file called output.txt. If the file does not exist, it will be created, and if it already exists, it will be overwritten. Next, the created ofs object is used in a similar manner to what is done with std::cout.

Several things can go wrong when working with files. It is, therefore, good practice to check if the file has been opened correctly. The following program will throw a runtime error because it tries to write to a file in a folder that does not exist

#include <fstream>

int main()

{

ofstream ofs{"fake_folder/output.txt"};

if (!ofs)

{

throw runtime_error("Unable to open file");

}

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

ofs << i << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Similar to iostream it is possible to read from a file using fstream. The following program writes to a file, then reads from it, and finally prints the output to the console

#include <fstream>

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

ofstream ofs{"output.txt"};

if (!ofs)

{

throw runtime_error("Unable to open file");

}

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

ofs << i << std::endl;

}

ifstream ifs{"output.txt"};

int x;

while (!ifs.eof())

{

ifs >> x;

std::cout << x << "\n";

}

return 0;

}

Note that ifs.eof() returns true when the end of the file is reached.

Comments#

Comments are often useful to add in places where you need to provide some extra information. In Python, we use the

#in front of the line with comments, while in C++, we use//.In C++, we can also have multiline comments beginning with

/*and ending with*/.